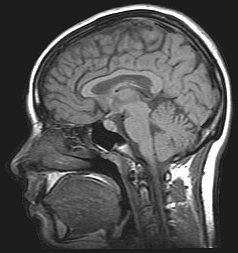

Oregon: Neuroimaging of the brain using technologies such as magnetic

resonance imaging, or MRIs, increasingly is showing promise as a

technique to predict adolescent vulnerability to substance abuse

disorders, researchers conclude in a new analysis. A greater understanding of what such technologies offer

and continued research to perfect the use of them may ultimately help

identify youth at the highest risk for these problems and allow

prevention approaches. These might include neuropsychological

intervention exercises that can strengthen vulnerable cognitive networks

in the brain.

The findings are of importance, researchers say, because underage

alcohol and drug use is increasingly being recognized as a public health

and social problem, with long-term consequences that include poorer

academic performance, neurocognitive deficits and psychosocial problems.

Youth who begin drinking before age 15 have four to six times the

rate of lifetime alcohol dependence than those who do not drink by age

21, researchers noted in this analysis, which was recently published in

Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences.

“Structural and neural alterations in the brain from drug and alcohol

abuse have now been well established,” said Anita Cservenka, an

assistant professor in the College of Liberal Arts at Oregon State

University, and co-author of the study.

“It’s also becoming clear that some of these alterations can exist

before any substance abuse, and often are found in youth who have a

family history of alcohol and drug use disorders. These familial risk

factors can play a role in future substance abuse, along with

environmental risk factors such as peer influence, personality and

psychosocial interactions.”

Family history of alcohol-use disorder is a strong predictor of

substance abuse, Cservenka said, as it raises the risk for the

development of alcohol-use disorder in adolescents by three to five

times. Neuroimaging studies show significant overlap in brain scans

between those with a family history of alcohol- and substance-use

disorders and youth who begin using substances during adolescence.

Some of the findings in youth with family history of alcohol- and

substance-use disorder include a smaller volume of limbic brain regions,

sex-specific patterns of hippocampal volume, and a positive association

of familial risk with “nucleus accumbens” volume in the brain. Other

risk factors for adolescent substance use that have been identified

include poorer performance on executive functioning tasks of inhibition

and working memory, smaller brain volumes in reward and cognitive

control regions, and heightened response to rewards.

A factor contributing to a peak in substance use during adolescence,

researchers say, may be emotion and reward systems that develop before

cognitive control systems, leaving youth more vulnerable to risk-taking

behaviors.

Almost two thirds of 18-year-olds, for instance, support lifetime

alcohol use; 45 percent marijuana use; and 31 percent smoking

cigarettes.

Various studies, Cservenka said, are examining such issues, including

the National Consortium on Alcohol and Neurodevelopment in Adolescence,

which includes five sites across the U.S. following 800 youth ages

12-21.

“We’re just beginning to understand the risk factors for substance

abuse and the consequences of adolescent substance use with these types

of large, long-term studies,” she said. “Ultimately such information

should help inform us about who might be at most risk and what brain

areas are most vulnerable, so we can target them and work to prevent the

problems.”

If an MRI showed weakness in working memory, for instance, computer

games or behavioral tasks might help strengthen the area of the brain

that is deficient. Similar approaches might also be used to help address

issues such as stress and depression, Cservenka said.

The lead author on this review was Lindsay Squeglia at the Medical

University of South Carolina. The work has been supported by the

National Institutes of Health.