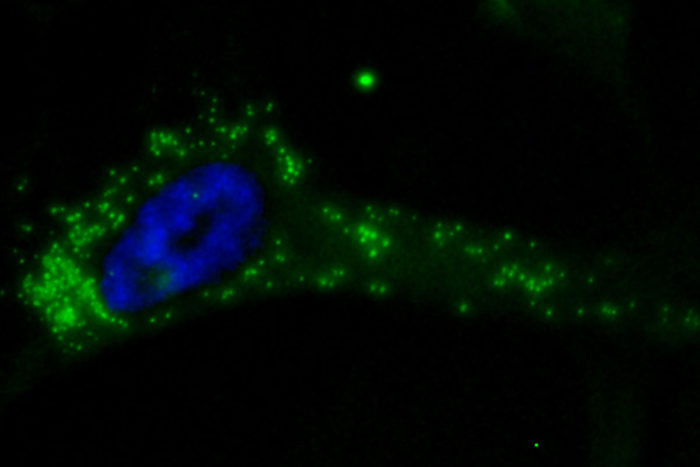

Saint-Louis: Unlike a

healthy cell, a sarcoma cell (above) relies on environmental sources of

arginine, an important protein building block. Remove environmental

arginine and the cell must begin a process called autophagy, or

"self-eating," to survive. A second hit to its survival pathways then

kills the cell, according to a new study at Washington University School

of Medicine in St. Louis. Areas of autophagy are shown in green and the

cell nucleus in blue. For decades, scientists have tried to halt cancer by blocking

nutrients from reaching tumor cells, in essence starving tumor cells of

the fuel needed to grow and proliferate. Such attempts often have

disappointed because cancer cells are nimble, relying on numerous backup

routes to continue growing.

Now, scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have exploited a common weak point in cancer cell metabolism, forcing tumor cells to reveal the backup fuel supply routes they rely on when this weak point is compromised. Mapping these secondary routes, the researchers also identified drugs that block them. They now are planning a small clinical trial in cancer patients to evaluate this treatment strategy.

The research is published Jan. 24 in Cell Reports.

Studying human cancer cells and mice implanted with patients’ tumor samples, the researchers demonstrate that a double hit — knocking out the weak point and one of the tumor cells’ backup routes — shows promise against many hard-to-treat cancers. Though present in multiple cancer types, the weak point is particularly common in sarcomas — rare cancers of fat, muscle, bone, cartilage and connective tissues. Doctors treat sarcomas primarily with traditional surgery, radiation and chemotherapy, but such treatments often are not effective.

“We have determined that this metabolic defect is present in 90 percent of sarcomas,” said senior author Brian A. Van Tine, MD, PhD, an associate professor of medicine. “Healthy cells don’t have this weakness. We have been trying to create a therapy that takes advantage of the metabolic defect because, in theory, it should target only the tumor. Basically, the defect allows us to force the tumor cells to starve.”

To grow and proliferate, tumor cells must have basic building materials. The researchers’ strategy relies on the fact that the vast majority of sarcomas have lost the ability to manufacture their own arginine, a protein building block that cells need to make more of themselves. Lacking this ability, the cells must harvest arginine from the surrounding environment. The supply of arginine in the blood is abundant, and cancer cells have no trouble scavenging it. But remove this environmental supply of arginine and the cells have a problem.

“When we use a drug to deplete arginine in the blood, the cancer cells panic because they’ve lost their fuel supply,” Van Tine said. “So they rewire themselves to try to survive. In this study, we used that rewiring to identify drugs that block the secondary routes.”

Unlike most cancer therapies, depleting arginine in the blood does not affect healthy cells. Normal cells don’t rely on external sources of arginine because they don’t have the cancer’s metabolic defect. They continue to make their own arginine, so there is no induced starvation in normal cells even when there is no arginine in the blood. Van Tine said this strategy is based on the properties of a tumor — it shuts down tumor metabolism specifically and nothing else.

Unable to make or obtain external arginine, the tumor cells’ fuel supply routes are forced inward. The cells must begin to metabolize their internal supply of arginine in a process called autophagy, or “self-eating.” In the case of sarcomas, this state slows or pauses cancer growth but does not kill the cell. During this period, tumor cells appear to be buying time to find yet another internal work-around.

“Cancer doesn’t die when you halt its primary fuel supply,” Van Tine said. “Instead, it turns on all these salvage pathways. In this paper, we identified the salvage pathways. Then we showed that when you drug them, too, you kill cells. Our study showed that tumors actually shrink under these conditions. This is the first time tumors have been shown to shrink using just metabolism drugs and no other anti-cancer strategies.”

The arginine-depleting drug is currently in clinical trials investigating its safety and effectiveness against liver, lung, pancreatic, breast and other cancers. But so far, it has been ineffective likely because it has activated the salvage pathways allowing cancer growth to continue. The researchers said the drug may yet become a vital metabolic therapy for cancer as long as it is used in combination with other drugs targeting the backup pathways.

Van Tine and the study’s first author, Jeff C. Kremer, a PhD student in Van Tine’s lab, explained that when cancer cells with this metabolic defect are deprived of environmental arginine, they are forced to shift from a system that burns glucose to a system that burns a different fuel called glutamine. They showed that adding a glutamine inhibitor to the arginine-depleting drug is lethal to the cells. Eliminating arginine from the blood also rewires serine biology, another backup fuel, so adding serine inhibitors also causes cell death.

This strategy could be applied beyond rare sarcoma tumors because the metabolic defect is often present in other cancers, including certain types of breast, colon, lung, brain and bone tumors, the researchers said. The new study includes data showing similar anti-tumor responses in cell lines from these cancer types. Van Tine also pointed out that all of the drugs used in the study are either already approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for other conditions or in ongoing clinical trials investigating cancer drugs.

Based on this study and related research, Van Tine and his colleagues at Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine are planning a clinical trial of the arginine-depleting drug in patients with sarcomas.

“We will start with a baseline trial testing the arginine-depleting drug against sarcomas with this defect, and then we can begin layering additional drugs on top of that therapy,” Van Tine said. “Unlike breast cancer, for example, sarcomas currently have no targeted therapies. If this strategy is effective, it could transform the treatment of 90 percent of sarcoma tumors.”