Saint-Louis: Scientists had thought that destroying acid-secreting cells in the

stomach would lead to a precancerous condition in other stomach cells.

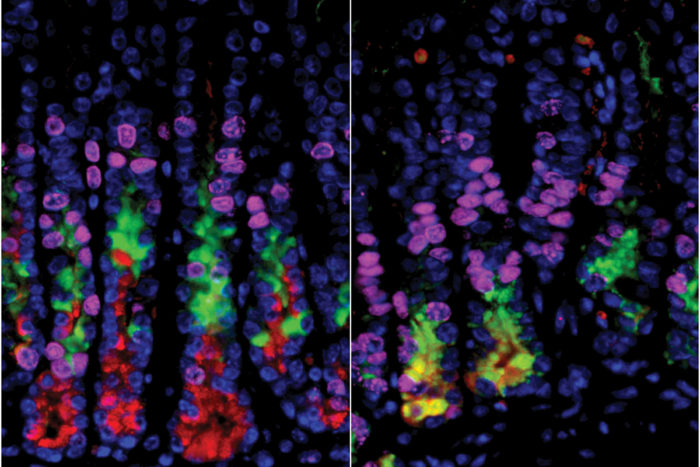

In the stomachs of mice, cells on the right (in yellow) are undergoing a

process that can lead to cancer. But on the left, where researchers

selectively had destroyed acid-secreting cells, the precancerous changes

did not happen. Conventional wisdom holds that the loss of cells that secrete acid in

the stomach leads to a condition that eventually can develop into

stomach cancer. But new research at Washington University School of Medicine and Siteman Cancer Center

at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University in St. Louis

indicates otherwise. Researchers found that damage to acid-secreting

cells alone doesn’t jump-start the transformation of healthy cells into

precancerous cells — at least in a mouse model.

Their research is published online in the journal Gastroenterology.

“We believe it’s easier to stop cancer from starting than to treat it

after it occurs, so our goal has been to find ways to stop this cascade

before it begins,” said first author and doctoral candidate Joseph

Burclaff. “But the first steps in the process that leads to cancer,

however, are different than what we had assumed, so to prevent cancer,

we’ll need to identify the real culprit.”

Burclaff works in the laboratory of Jason C. Mills, MD, PhD, a professor of medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology.

Like other scientists in the field, they had concluded long ago that

damage to acid-secreting cells in the stomach leads directly to a

precancerous condition called metaplasia. But studying a mouse model of

that condition, the researchers learned that the conventional wisdom was

wrong.

“We thought we had this process figured out, but when we selectively

destroyed only these acid-secreting cells in the stomachs of mice, the

animals didn’t develop metaplasia,” Mills said.

The precancerous process causes cells in adult organs to change in

response to inflammation or injury. Those changes may help cells respond

more effectively to particular types of injury. The problem, said

Mills, who also is a professor of developmental biology and of pathology

and immunology, is that when the process continues over many years, it

greatly increases cancer risk.

The two main causes of the precancerous condition are bacterial infections — particularly with H pylori, the microbe associated with stomach ulcers — and inflammation caused by the body’s own immune system.

In this study, Burclaff and Mills inserted a human gene into

acid-secreting cells in the stomachs of mice. Then, by exposing the

animals to a toxin that affects human cells but not mouse cells, they

were able to kill the acid-secreting cells without damaging any other

cells in the animals. But, surprisingly, the mice did not go on to

develop the precancerous condition.

“We had thought the dying cells might signal other cells, sort of

like a 911 call,” Burclaff said. “If there was such a signal, we could

work to block it before it led to cancer. But these experiments

demonstrate that if such signals exist, they must be coming from

someplace else.”

Burclaff and Mills now believe whatever is contributing to the

precancerous condition also may be causing the acid-secreting cells to

die.

“These experiments suggest the loss of the acid-secreting cells and

metaplasia may occur through different mechanisms,” Mills said.

“Ultimately, the cause may be the same, for example infection with H pylori,

but simply damaging or destroying the cells isn’t sufficient to launch

this cascade. The more we can learn about what actually causes the

precancerous condition, the more likely we’ll be able to interrupt the

cascade and prevent stomach cancer.”