RSNA: A new MRI study has found distinct injury patterns in the brains of

people with concussion-related depression and anxiety, according to a

new study published online in the journal Radiology. The findings may lead the way to improved treatment and understanding of these common disorders, researchers said.

Post-concussion psychiatric disorders like depression, anxiety and

irritability can be extremely disabling for those among the nearly 3.8

million people in the United States who suffer concussions every year.

The mechanisms underlying these changes after concussion—also known as

mild traumatic brain injury—are not sufficiently understood, and

conventional MRI results in most of these patients are normal.

For the new study, researchers from the University of Pittsburgh

Medical Center (UPMC) in Pittsburgh used diffusion tensor imaging (DTI),

an MRI technique that measures the integrity of white matter—the

brain's signal-transmitting nerve fibers—to see if injuries to the

nerves may be the root cause of these post-traumatic depression and

anxiety symptoms.

The researchers obtained DTI and neurocognitive testing results for

45 post-concussion patients, including 38 with irritability, 32 with

depression and 18 with anxiety, and compared the results with those of

29 post-concussion patients who had no neuropsychiatric symptoms.

"Using other concussion patients as our controls was a big advantage

of our study," said lead author Lea M. Alhilali, M.D., assistant

professor of radiology at UPMC. "When you are able to study a similar

population with similar risk factors, you get much more reliable

results."

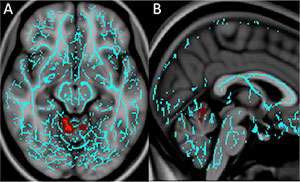

The researchers saw unique white matter injury patterns in the

patients who had depression or anxiety. Compared to controls, patients

with depression had decreased fractional anisotropy (FA), a measure of

the structural integrity of white matter connections, around an area

near the deep gray matter of the brain that is strongly associated with

the brain's reward circuit.

"The regions injured in concussion patients with depression were very

similar to those of people with non-traumatic major depression

disorder," Dr. Alhilali said. "This suggests there may be similar

mechanisms to non-trauma and trauma-dependent depression that may help

guide treatment."

Anxiety patients had diminished FA in a part of the brain called the

vermis that helps modulate fear-related behaviors. Since the vermis has

not been associated with dysfunction in non-traumatic anxiety disorders,

this finding may indicate that different treatment targets are required

for patients with anxiety after trauma, the researchers said.

No regions of significantly decreased FA were seen in patients with irritability relative to the control subjects.

"There are two major implications for this study," Dr. Alhilali said.

"First, it gives us insight into how abnormalities in the brain occur

after trauma, and second, it shows that treatments for non-trauma

patients with neuropsychological symptoms may be applicable to some

concussion patients."

The study also raises the possibility that some people diagnosed with

non-traumatic depression may actually have experienced a subclinical

traumatic event at some point earlier in their lives that may have

contributed to the development of depression, she noted.

In the future, the researchers hope to compare DTI findings in

concussion patients with depression to those of people who have

non-trauma-related depressive disorders.