After an infection with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), the virus persists in the body throughout a person’s lifetime, usually without causing any symptoms. About one third of infected teenagers and young adults nevertheless develop infectious mononucleosis, also known as glandular fever or kissing disease, which usually wears off after a few weeks. In rare cases, however, the virus causes cancer, particularly lymphomas and cancers of the stomach and of the nasopharynx.

Scientists have been trying for a long time to elucidate how the viruses reprogram cells into becoming cancer cells. “The contribution of the viral infection to cancer development in patients with a weakened immune system is well understood ” says Henri-Jacques Delecluse, a cancer researcher at the German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ) in Heidelberg. “But in the majority of cases, it remains unclear how an EBV infection leads to cancer development.”

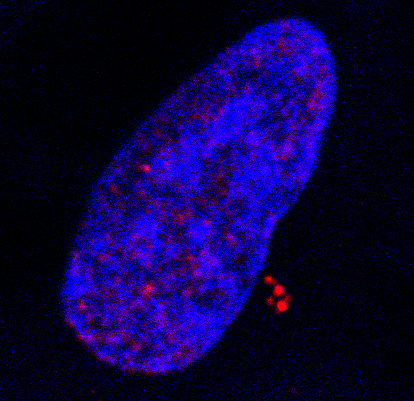

In their present publication, Delecluse, in collaboration with Ingrid Hoffmann, also from the DKFZ, and their respective groups present a new and surprising explanation for this phenomenon. The scientists have shown for the first time that a protein component of the virus itself promotes the development of cancer. When a dividing cell comes in contact with Epstein-Barr viruses, a viral protein present in the infectious particle called BNRF1 frequently leads to the formation of an excessive number of spindle poles (centrosomes). As a result, the chromosomes are no longer divided equally and accurately between the two daughter cells – a known and acknowledged cancer risk factor. By contrast, Epstein-Barr viruses that had been made deficient of BNRF1 did not interfere with chromosome distribution to the daughter cells.

EBV, a member of the herpes virus family, infects B cells of the immune system. The viruses normally remain silent in a few infected cells, but occasionally they reactivate to produce viral offspring that infects nearby cells. As a consequence, these cells come in close contact with the harmful viral protein BNRF1, thus having a greater risk of transforming into cancer cells.

“The novelty of our work is that we have uncovered a component of the viral particle as a cancer driver,” Delecluse said. “All human tumors viruses that have been studied so far cause cancer in a completely different manner. Usually, the genetic material of the viruses needs to be permanently present in the infected cell, thus causing the activation of one or several viral genes that cause cancer development. However, these gene products are not present in the infectious particle itself”.

Delecluse and his colleagues therefore suspect that EBV could cause the development of additional tumors. These tumors might have previously not been linked to the virus because they do not carry the viral genetic material.For Delecluse, the consequence that follows from his findings is immediate: “We must push forward with the development of a vaccine against EBV infection. This would be the most direct strategy to prevent an infection with the virus. Our latest results show that the first infection could already be a cancer risk and this fits with earlier work that showed an increase in the incidence of Hodgkin’s lymphoma in people who underwent an episode of infectious mononucleosis.”

Experts estimate that an EBV vaccine could prevent two percent of all cancer cases worldwide. Delecluse and his group already developed a vaccine prototype in 2005. It is based on so-called ‘virus-like particles’, or VLPs. These are empty virus shells that mimic an EBV infectious particle, thus prompting the body to mount an immune response. However, “Of course, the VLPs must not contain BNRF1!” Delecluse hastens to add.