University of Florida researchers have identified a subtype of a

specific receptor in the brain that is critical for “working memory,” or

the ability to hold information in mind for a short time — an ability

that often diminishes with normal aging. In a new study published this

week in The Journal of Neuroscience, the UF team details how the loss of

that specific receptor predicts the severity of working-memory

impairment due to aging. The researchers further found they could use a drug to positively

affect those receptors to enhance working memory in aged rats with

cognitive decline. The findings suggest a potential future pathway for

drug treatment to target those receptors and improve working memory in

humans.

“Working memory is the ability to hold information in mind for a

relatively short duration, for example, the ability to look up a phone

number and remember it until you get to the phone,” said principal

investigator Jennifer L. Bizon, Ph.D., a professor of neuroscience and

psychiatry in the Evelyn F. and William L. McKnight Brain Institute of

the University of Florida. “The ability to do that simple process of

holding information over a period of about 30 seconds is critical for

planning and carrying out daily activities and is the foundation for

more complex cognitive operations such as decision-making.

“We know across species — rats, non-human primates and people — that

working memory declines over the course of the lifespan,” Bizon said.

“It’s also very vulnerable in a number of neuropsychiatric diseases,

such as schizophrenia.”

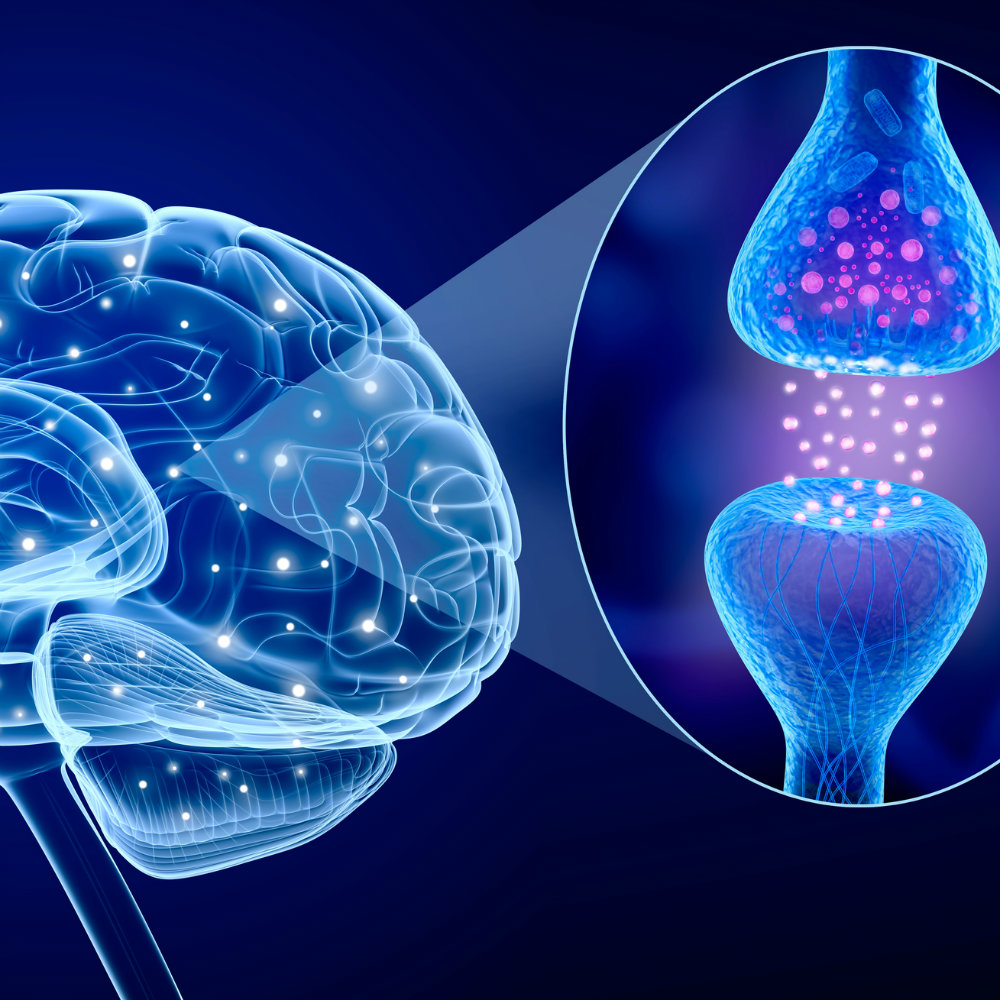

Previous studies have pointed to receptors for the neurotransmitter

glutamate in working memory function. The new UF study, led by

postdoctoral fellow Joseph A. McQuail, is significant because it

identifies glutamate receptors containing a specific protein subunit as

critical for working memory and its decline across the lifespan.

“Many treatments have sought to broadly modulate these receptors to

improve working memory in schizophrenia and other neuropsychiatric

diseases and have not been successful,” Bizon said.

The new findings “give us a more selective target for treating working memory deficits,” she said.

The UF research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the

National Science Foundation and the McKnight Brain Research Foundation.