INSERM: To protect against attack, the body uses natural repair processes.

What is involved in the spontaneous regeneration of the myelin sheath

surrounding nerve fibres? This is the question addressed by researchers

in Unit 1195, “Neuroprotective, Neuroregenerative and Remyelinating

Small Molecules” (Inserm/Paris-Sud University). They have discovered, in

mice, the unexpected regenerative role of testosterone in this process.

This could be a factor in the progression of demyelinating diseases,

such as multiple sclerosis, which can present differently in women and

men, and heralds new therapeutic opportunities.

These results are published in PNAS.

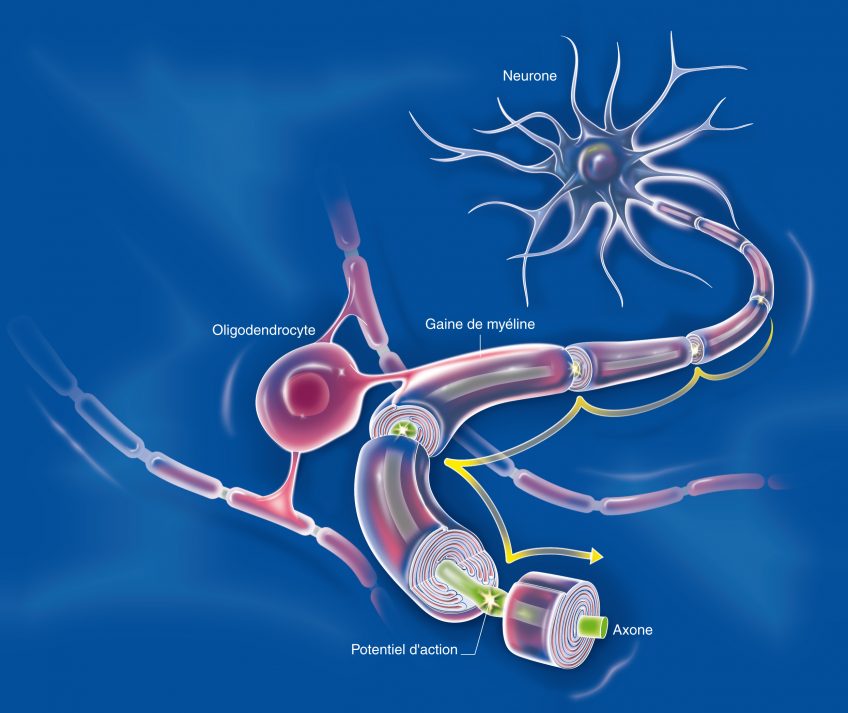

The myelin sheath allows the rapid transmission of information

between the brain or spinal cord and the rest of the body. Myelin may be

targeted by conditions known as demyelinating diseases, such as

multiple sclerosis or injuries that lead to its destruction. These

diseases disrupt neurotransmission, leading to various symptoms

including paralysis. Repair mechanisms then come into play, and bring

about myelin regeneration and resolution of symptoms. This regenerative

process is erratic, for reasons that are still largely unknown. This

question was analysed by the research team “Myelination and Myelin

Repair” in Unit 1195, “Neuroprotective, Neuroregenerative and

Remyelinating Small Molecules.”

In this study, the researchers present evidence of the unexpected

central role of the well-known male sex hormone, testosterone, and of

its receptor, the androgen receptor, in spontaneous myelin repair.

“Testosterone promotes the production of myelin by the cells that

synthesise it in the central nervous system, in order to repair the

sheath, which is essential to the transmission of nerve impulses,” explains Elisabeth Traiffort, Inserm Research Director.

In the absence of testes and hence of the hormone, testosterone, that

these organs produce, the spontaneous myelin repair process is

disrupted in mice. Indeed, the maturation of cells specialised in myelin

synthesis, known as oligodendrocytes, is defective. The researchers

also showed that control of this maturation, provided by astrocytes,

another type of cell with an important role in repair, is what is

compromised.

But why testosterone? Returning to the origins of this hormone, it

turns out, surprisingly, that the androgen receptor that enables

testosterone to act appeared at the same time as myelin, very late in

the evolution of gnathostomes (vertebrates with jaws). According to the

researchers, this would explain their very strong association in the

myelination process.

“It is perhaps also one of the reasons why progression of

demyelinating diseases such as multiple sclerosis often differs between

men and women. Our results pave the way for new therapeutic

opportunities, and might also benefit research on psychiatric diseases

or cognitive ageing,” concludes Elisabeth Traiffort, Inserm Research Director.