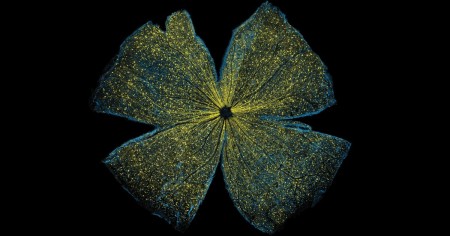

NIH: The retina, like this one from a mouse that is flattened out and

captured in a beautiful image, is a thin tissue that lines the back of

the eye. Although only about the size of a postage stamp, the retina

contains more than 100 distinct cell types that are organized into

multiple information-processing layers. These layers work together to

absorb light and translate it into electrical signals that stream via

the optic nerve to the brain. In people with inherited disorders in which the retina degenerates,

an altered gene somewhere within this nexus of cells progressively robs

them of their sight.

This has led to a number of human clinical

trials—with some encouraging progress being reported for at least one

condition, Leber congenital amaurosis—that are transferring a normal

version of the affected gene into retinal cells in hopes of restoring

lost vision.

To better understand and improve this potential therapeutic strategy,

researchers are gauging the efficiency of gene transfer into the retina

via an imaging technique called large-scale mosaic confocal microscopy,

which computationally assembles many small, high-resolution images in a

way similar to Google Earth. In the example you see above,

NIH-supported researchers Wonkyu Ju, Mark Ellisman, and their colleagues

at the University of California, San Diego, engineered adeno-associated

virus serotype 2 (AAV2) to deliver a dummy gene tagged with a

fluorescent marker (yellow) into the ganglion cells (blue) of a mouse

retina. Two months after AAV-mediated gene delivery, yellow had overlaid

most of the blue, indicating the dummy gene had been selectively

transferred into retinal ganglion cells at a high rate of efficiency

[1].

The researchers also used AAV2 to deliver

into the retinas of mice a gene that coded for a mutant version of a

protein, called DRP1. They found it inhibited normal DRP1 protein and

stopped retinal ganglion cells from dying in response to glaucoma, a

vision-threatening condition that elevates pressure within the eye. The

gene transfer proved successful in rescuing the retinal ganglion cells,

and researchers are continuing to pursue this line of study with the aim

of translating their discoveries into possible ways of helping humans

with glaucoma.

It’s also worth noting that this image recently took top honors in

the NIH Institute and Centers Art Challenge, which was held in October

as part of the Combined Federal Campaign, in which federal employees

make their annual contributions to charitable organizations. The art

competition had a number of outstanding entrants, some of which will be

on display during November at the NIH Clinical Center in Bethesda, MD.

If you’re in the neighborhood, come take a look!

References:

[1] DRP1

inhibition rescues retinal ganglion cells and their axons by preserving

mitochondrial integrity in a mouse model of glaucoma. Kim KY, Perkins GA, Shim MS, Bushong E, Alcasid N, Ju S, Ellisman MH, Weinreb RN, Ju WK. Cell Death Dis. 2015 Aug 6;6:e1839.