Saint Louis: Some 10 million points of genetic variation are scattered across a

molecule of DNA, and those variations make us who we are as individuals.

But in some cases, those variants contribute to diseases, and it’s a

major challenge for scientists to distinguish between harmless variants

and those that are potentially hazardous to our health. Now, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St.

Louis have developed a new technique to cheaply and rapidly create

myriad sets of DNA fragments that detail all possible genetic variants

in a particular stretch of DNA. By studying such DNA fragments,

scientists can more easily distinguish between genetic variants linked

to disease and those that are innocuous.

The findings, published Oct. 3 in Nature Methods, allow researchers

to create sets of DNA variants in a single day for a few hundred

dollars. Current methods take up to a week and cost tens of thousands of

dollars.

“As a pediatric neurologist who does a lot of genetic studies of kids

with developmental disabilities, I frequently will scan a patient’s

whole genome for genetic variants,” said Christina Gurnett, MD, PhD, the

study’s senior author and an associate professor of neurology and of

pediatrics. “Sometimes I’ll find a known variant that causes a

particular disease, but more often than not I find genetic variants that

no one’s ever seen before, and those results are very hard to

interpret.”

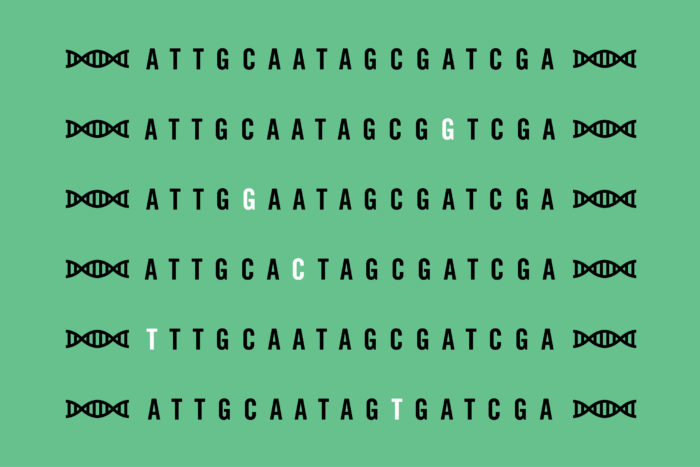

In the past, scientists tested the effect of genetic variants one by

one, a laborious process. At a single point in the DNA sequence, they

replaced the correct DNA letter – an A, T, C or G – with one of the

other three options. Then, they translated that DNA sequence into a

protein and evaluated whether the mutated protein behaved differently

than the original one.

More recently, researchers have begun creating sets of hundreds of

variants in which each letter in a particular DNA sequence is changed,

and then testing the set all at once. Such studies have been limited,

however, by the high cost of creating those sets.

Postdoctoral researcher Gabriel Haller, PhD, who was working in

Gurnett’s lab, realized that he could harness common laboratory

techniques and tools to create sets of DNA variants without the

expensive equipment and reagents that drove up the price.

Haller copied a DNA sequence using the four standard DNA letters and a

nonstandard letter known as inosine. Each copy of the sequence was

identical except for one inosine, which was located at a random spot and

served as a placeholder. Then, he replaced the inosine with one of the

standard DNA letters, creating a single mutation in each copy of the

sequence.

Gurnett and colleagues are applying this technique to genes

associated with aortic aneurysms, a weakening and ballooning of the

aortic wall that can be fatal. Over the long term, Gurnett envisions

the creation of a catalog listing the effects of every possible variant.

The speed and cheapness of the new technique make such a catalog

possible.

“Then, when clinicians find a variant that’s never been seen before

in one of these genes associated with aortic aneurysm, they can go

through this catalog and say, ‘Yes, this mutation does have a negative

effect on that protein, so it’s likely harmful’,” Gurnett said. “It

would help them decide what to tell the patient. This would be one piece

of the big interpretation puzzle for genetic mutations.”