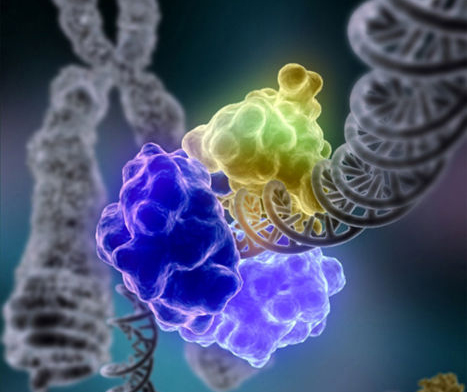

Pittsburgh: Research by scientists at the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute

(UPCI) has revealed how cancer cells hijack DNA repair pathways to

prevent telomeres, the endcaps of chromosomes, from shortening, thus

allowing the tumor to spread. The findings are published today in the

journal Cell Reports. The moment a cell is formed, a countdown clock starts ticking that

determines how long the cell can live. The clock is the telomere, a

series of repeating DNA letters at the ends of each chromosome in the

cell.

However, cancer cells cleverly hijack this telomere clock,

resetting it and lengthening the telomere every time it shortens. This

leads the cell into thinking that it is still young and can divide,

spreading the tumor.

Most cancers do this by increasing the activity of an enzyme called

telomerase which lengthens telomeres. But approximately 15 percent of

cancers use a different mechanism for resetting the clock, called

alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT).

Growing evidence also suggests that tumors that activate the ALT

pathway are aggressive and more resistant to treatment. Although ALT was

identified close to two decades ago, identifying how this mechanism

works has proved elusive.

“Identifying the parts that the cancer cell tweaks to reset the

countdown timer could provide targets for developing new cancer drugs or

making existing ones more effective,” said senior author Roderick

O’Sullivan, Ph.D., assistant professor of pharmacology and chemical

biology at Pitt’s School of Medicine and a member of UPCI.

O’Sullivan and his team tackled this problem by using a recently

developed technique called proximity dependent biotinylation (BioID),

which allowed them to quickly identify proteins that were physically

close to, and hence potentially associated with, telomere lengthening in

cancer cells.

When comparing cancer cells in which either telomerase or ALT were

active, the BioID technique identified 139 proteins that were unique to

ALT-activated cells. As the research team took a closer look, one

enzyme, DNA polymerase η (Polη), took them by surprise.

“We expected to see DNA repair proteins, but seeing Polη was really

unexpected as it was known to be activated only in cells that were

damaged by UV light, which we did not use in our experiments. Its role

in the ALT pathway is completely independent of how we think of it

normally,” said O’Sullivan. Knowing the molecular players in the ALT

pathway opens up a whole new area of research and many potential drug

targets, according to O’Sullivan.

Laura Garcia-Exposito, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in O’Sullivan’s

lab, and Elodie Bournique, a graduate student in the laboratory of Dr.

Jean-Sébastien Hoffmann at the Cancer Research Center of Toulouse,

France, are the co-first authors of the study.

Other study authors include Arindam Bose, Ph.D., Simon C. Watkins,

Ph.D., Patricia Opresko, Ph.D., Callen Wallace and Justin L. Roncaioli,

all of the University of Pittsburgh; Valérie Bergoglio, Ph.D., and

Jean-Sébastien Hoffmann Ph.D., of the Cancer Research Center at the

University of Toulouse; Sufang Zhang, Ph.D., and Marietta Lee Ph.D., of

New York Medical College.

This research was funded by grants from the Competitive Medical

Research Fund and Stimulating Pittsburgh Research in Geroscience at the

University of Pittsburgh, National Institutes of Health grants ES022944, P30CA047904, 1S10OD019973-O1; and INCa-PLBIO 2016, ANR PRC 2016, Labex Toucan, and La Ligue contre le Cancer.