Authors: Drs Marshall Stoller (university of California SF) and Aaron Berger (Chicago) 2009-12-10

Introduction:

The

kidneys are paired organs with the primary function of helping to remove

toxins from the body and regulate water balance; they are vital to

survival. After urine is produced in the kidneys, it must

pass down to the bladder where it can be stored before being eliminated

from the body through the urethra. At almost any point in this pathway, urine can become obstructed and may lead to kidney damage. When severe, this can cause a patient to require a kidney transplant or dialysis to sustain life. Obstruction can be present from birth or it may develop later in life. The most common causes of obstruction include stones, strictures, tumors, and bladder dysfunction. This article will discuss the various causes and treatments of urinary tract obstruction.

Relevant Anatomy:

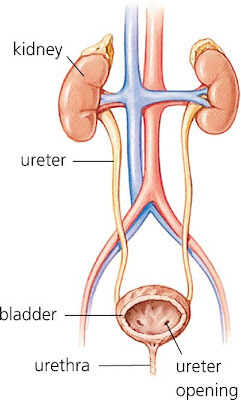

The

urinary tract has several main components including the kidneys which

form the urine, the ureters which transport the urine to the bladder,

which then stores the urine until it passes out of the body through the

urethra.

The kidneys are paired, bean shaped organs located in the back just below the ribs. They

serve multiple functions in the body, but primarily the kidneys filter

the blood to clear toxins and extra water from the body by producing

urine. Blood is filtered by a specialized structure called the glomerulus. Filtered

blood from the glomeruli passes into a complex and highly specialized

tubular system that runs through the kidney called the nephron that

adjusts the concentration of the urine, and is responsible for the

excretion or absorption of the various electrolytes such as sodium and

potassium. There are three main parts of the kidney .

The

cortex is the outer portion of the kidney where all the specialized

filters (glomeruli) and tubular structures (nephrons) that filter the

blood and concentrate the urine are located. The medulla is where the final concentration of the urine is adjusted prior to entering the collecting system. The

collecting system is where the urine empties before passing down the

ureters, which are the long thin tubes (about 2-4mm in diameter and

25-30cm in length) that channel the urine into the bladder. The

collecting system is comprised of a branch network of structures called

calyces which all empty into the renal pelvis, which then funnels the

urine into the ureters. The ureters empty into the bladder where the urine is stored until the urine is eliminated from the body through the urethra. Obstruction

may occur along almost any point in this pathway and can lead to

symptoms such as pain, nausea, vomiting, fevers, chills and,

potentially, damage to the kidneys.

Signs, Symptoms, Diagnosis:

The hallmark of urinary tract obstruction is dilation of the collecting system of the kidney which is known as hydronephrosis. This swelling typically causes pain in the flank or upper abdomen on the affected side. Sometimes, the pain may be severe enough to cause nausea or even vomiting.

When hydronephrosis is present, the kidney is not draining urine normally so there can be stasis (slowing or stopping of the flow) of urine in the collecting system. This may lead to urinary tract infection or stone formation so patients may present with signs of infection such as fevers, chills, or pain or burning with urination (dysuria).

The evaluation of urinary

tract obstruction often includes a urinalysis to look for: signs of

infection, blood in the urine, a white blood cell count which if

elevated can signify infection, and a serum creatinine level which is an

approximate measure of total kidney function and is often elevated in

cases of obstruction. There are multiple imaging modalities that can be used in the diagnosis of urinary tract obstruction. Ultrasound

is readily available, causes no radiation exposure, and can easily

identify hydronephrosis, but may not always be able to identify the

cause. Ultrasound may be used to determine if the bladder is distended and a possible source of hydronephrosis. An

intravenous urogram (IVU) is a study where the patient is given a

contrast dye injection and then plain x-rays are taken at several points

in time. This study used to be very commonplace and

provides useful information, but has been replaced for the most part by

computed tomography (CT). CT scans can be performed with

and without intravenous contrast and can provide useful information not

only about the urinary tract, but other intra-abdominal organs as well,

which can enable the practitioner to look for other types of pathology

which may be causing obstruction. Magnetic resonance

imaging is also a useful modality in the evaluation of urinary tract

obstruction, but it has the disadvantage of being more costly, less

readily available, more time consuming, and it does not detect kidney

stones very well. In many cases of urinary tract obstruction, a nuclear renal scan is obtained. During

this exam, a radiotracer (a radioactive solution) is given

intravenously and then scans are performed at multiple time points. The

figure below shows a normal kidney on the right and an obstructed

kidney on the left as the tracer concentrates slowly and does not drain

from the kidney.

These

studies provide useful information about the function of the kidneys in

relation to one another and help clarify how severe the obstruction is.

Urinary Stone Disease:

Stones

may occur in any part of the urinary tract and affect roughly 10% of

the population. (A detailed discussion of stone disease and treatment

can be found in the kidney stone Knol ) Stones typically

cause obstruction as they pass from the kidney, down the ureter toward

the bladder, but larger stones may obstruct a portion of the kidney or

the entire kidney if they are located in the renal pelvis. The

three most common locations for stones to cause obstruction are at the

point where the renal pelvis joins with the ureter (ureteropelvic

junction), the point where the ureters pass over the iliac artery and

vein in the pelvis, and where the ureter joins the bladder

(ureterovesical junction). There are multiple types of

stones but the majority of stones, with the exception of uric acid

stones, cannot be dissolved with medications and must either pass out of

the body on their own or be removed with a urologic intervention. Small

stones (less than 5mm) have a strong likelihood of passing into the

bladder and subsequently out of the urethra, but the chances decrease

dramatically with larger stones. Stone passage can be

aided by several medications including alpha-blockers (tamsulosin

(Flomax), alfuzosin (Uroxatral), terazosin (Hytrin), doxazosin

(Cardura)), steroids (prednisone, methylprednisolone), and non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory medications (ibuprofen, naproxen). All of these help

decrease inflammation and relax the smooth muscle in the ureter to help

stones pass. If medical expulsion therapy fails, there are multiple surgical options for treatment of stones. If

the patients are very sick, a drainage procedure to relieve the

obstruction is performed and this can either be with a ureteral stent or

a nephrostomy tube. A stent is a small plastic straw-like tube placed into the ureter to allow urine to drain past an obstructing stone.

A

nephrostomy tube is a small drainage tube placed directly into the

kidney through the skin of the back which allows the kidney to drain. For

definitive management of the stones, the options include shock wave

lithotripsy (SWL), ureteroscopy, percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PNL), or

open surgical removal.

Shock wave

lithotripsy is a non-invasive procedure during which a patient lies on a

special table and shock waves are targeted at the stone with a goal of

fragmenting the stone into tiny pieces which may subsequently pass.

Ureteroscopy

is a minimally invasive procedure during which a small scope is placed

into the bladder, the opening to the ureter is identified, and then a

smaller scope (ureteroscope) is placed into the ureter. The stone is then visualized and broken up with a laser or with other means and removed with a basket or graspers.

During

a percutaneous nephrolithotomy, a tract is formed directly into the

kidney from the back and stones are broken up and suctioned out using a

variety of devices. This procedure requires a small incision in the back and is often reserved for larger and/or more complex stones.

In

most cases, after the obstructing stone has passed or has been removed,

the kidney function returns to normal but in some cases of longstanding

obstruction, permanent loss of kidney function can occur. It is unclear how long a kidney may remain obstructed and still retain viable function.

Ureteropelvic Junction Obstruction (UPJO):

The

ureteropelvic junction is where the renal pelvis joins with the ureter

as urine is funneled out of the kidney into the ureter.

Obstruction

of the UPJ can be congenital or acquired. It can cause significant

obstruction of the affected kidney and may lead to loss of kidney

function over time.

The congenital

causes of UPJO are thought to be due to either a weak segment of ureter,

a section with abnormal muscle development so urine is not propelled

downwards, or a crossing blood vessel or tissue band which can cause

obstruction. It is unusual for children presenting with

UPJ obstruction to have a crossing vessel, although they are present in

about half of patients who present as adults. Acquired causes can be due to kidney stones or prior surgical interventions which can cause subsequent scarring.

UPJ obstructions may be asymptomatic or they may present with pain, nausea, vomiting, or urinary tract infections. Patients

with symptomatic UPJO often complain of worsening pain after drinking

large amounts of fluid, especially alcohol which is a diuretic and

causes the kidney to fill with urine more quickly thereby worsening the

distention. The age at presentation of UPJO is highly

variable with some cases being diagnosed on prenatal ultrasonography and

others not presenting until late in life; it is unclear exactly what

triggers the onset of symptoms.

Imaging

of the affected kidney with ultrasound or computed tomography (CT)

scanning demonstrates swelling of the collecting system

(hydronephrosis). A nuclear renal scan is often utilized

to assess not only the function of the obstructed kidney, but also the

degree of obstruction. During this test, radiotracer is injected intravenously (in the vein) and then several scans are performed over time. A

normal kidney will take up the radiotracer quickly and then excrete it

into the urine and down into the bladder in a matter of several minutes. In

a kidney with an UPJO, the uptake of tracer can be decreased if there

is functional damage to the kidney and there is often poor drainage of

the tracer from the kidney, which is indicative of obstruction.

There are several treatment options for a UPJO. For

symptomatic patients awaiting definitive repair or patients unable to

undergo more extensive surgery, a ureteral stent or a nephrostomy tube

can relieve the obstruction.

Another

more definitive treatment option is an endopyelotomy which can be

performed either in a retrograde fashion (from the bladder up towards

the kidney) with an ureteroscope or in an antegrade fashion via a

percutaneous approach similar to that discussed earlier for the

treatment of stones. During an endopyelotomy, a full

thickness incision is made in the lateral aspect of the diseased UPJ

with a knife, laser, or electrocautery device. A stent is

then typically left in place for 2-6 weeks to allow for healing and is

subsequently removed. These procedures have a long term success rate of

approximately 70-75% meaning that post-operatively, the UPJ drains well

and patients have symptomatic and radiographic improvement. The success of endopyelotomy decreases in cases with a crossing vessel.

Another

treatment option is a pyeloplasty which can either be performed open,

typically with an incision through the flank, or laparoscopically using

only three or four small (about 1cm) incisions in the abdomen. During

the most common form of pyeloplasty, the diseased segment of the UPJ is

completely excised and the ureter is then reattached to the renal

pelvis.

If

there is a crossing vessel, the ureter/renal pelvis is transposed above

(anterior) to the vessel to avoid recurrent obstruction. The

success rate for either open or laparoscopic pyeloplasty is better than

90% in most published reports and appears to be durable over the long

term. A successful outcome is usually based on symptomatic improvement for the patient but may also include radiographic improvement. A ureteral stent is typically left in place for several weeks after a pyeloplasty to allow the reconstructed UPJ to heal. If

the kidney no longer has much function due to long standing

obstruction, the best option may be to just remove the kidney,

especially if the patient has a history of recurrent urinary tract

infections and/or pain. Again, the kidney may be removed

either with a traditional open approach or may be done laparoscopically

which offers more rapid recovery with improved cosmetic results (see

Laparoscopic Renal Surgery Knol).

Ureteral Strictures

Strictures may occur anywhere in the ureter and are often the result of stones or prior surgery leading to scar tissue. Some infections diseases, however, such as tuberculosis may also cause scarring of the ureter. Strictures

may occur at the distal portion of the ureter, especially in cases

where ureteral reconstruction has occurred such as in kidney transplants

where the donated ureter is attached to the bladder. Another example of this is in patients with invasive bladder cancer where the bladder has been surgically removed. In

these cases, the ureters are usually connected to an isolated segment

of bowel which is used to create a new bladder or a conduit to the skin

for the urine to drain, and these are known as ureteroenteric

anastomotic strictures.

Similar to a

UPJ obstruction, ureteral strictures or ureteroenteric anastomotic

strictures can often be managed with a minimally invasive approach

either via an ureteroscopic or percutaneous approach. The

strictures can be incised with a laser, an endoscopic knife, an

electrocautery probe, or they may be dilated with a ureteral balloon

dilator. These techniques work well for short strictures

(less than 1cm) but for longer strictures, more extensive procedures are

required for long term success.

For

longer strictures in the distal ureter, a ureteral reimplantation can be

performed and may be combined with a procedure called a psoas

hitch/Boari flap. In these procedures, the ureter is disconnected from the bladder and the diseased segment is excised. The

bladder is then freed up from some of its attachments; this often

provides enough length to reach the more proximal healthy ureter and the

ureter is sewn back into the bladder. If the distance is

too far to bridge, a bladder flap is created and rotated up toward the

ureter and then sewn into a tube which is called a Boari flap. During this procedure, the bladder is fixed to the psoas muscle tendon to reduce tension on the repair (psoas hitch). Some

strictures in the mid or proximal ureter may be repaired by simply

excising the narrowed segment and sewing the two ends of the ureter back

together, a procedure known as a ureteroureterostomy For long

strictures in the proximal portion of the ureter, the ureter may be

replaced by a segment of intestine (ileal interposition) or the kidney

may be removed and then transplanted into the patient’s pelvis near the

bladder (auto-transplantation).

Obstruction from Malignancy:

The ureters may be affected by cancers occurring both inside and outside the urinary system. Almost

the entire urinary tract is lined by cells known as transitional cells

and these may develop cancers known as transitional cell carcinomas

(TCC) or urothelial carcinoma. TCC most commonly occurs in the bladder but may also occur in the ureter or in the collecting system of the kidney. Tumors of the ureter and larger tumors in the renal pelvis may lead to obstruction of the kidney.

The

recommended treatment for cancer in the ureter or collecting system of

the kidney is a nephroureterectomy where the kidney and the entire

ureter are removed all the way down to the bladder. The

reason for this is that urothelial carcinoma is thought to be a defect

of the entire lining of the kidney, ureter, and bladder known as a field

change defect and a tumor in the ureter has a high likelihood of

recurring in the kidney and the bladder. This procedure may be performed in either an open or laparoscopic fashion.

For

patients who cannot tolerate this relatively large operation or those

with a solitary kidney or other risk factors for poorly functioning

kidneys such as high blood pressure or diabetes mellitus, a minimally

invasive approach can be utilized. Tumors in the ureter or

collecting system of the kidney can be resected or fulgurated

(destroyed by electric current) with either cautery or laser via an

ureteroscopic or percutaneous approach. Patients treated with these techniques require frequent surveillance as these tumors often recur. Occasionally, large tumors in the bladder may cause obstruction of one or both ureteral orifices and lead to kidney obstruction. In these cases, resection of the bladder tumor is necessary to relieve the blockage.

There are a variety of malignancies which may cause obstruction of the urinary tract by compressing the ureter from the outside. In

these cases, the best and often only way to treat the obstruction is to

try to reduce the size of the cancer either surgically or with

chemotherapy or radiation.

Retroperitoneal Fibrosis (RPF):

The

kidneys and ureters are located in what is known as the

retroperitoneum, which means behind the peritoneal sac which contains

the majority of the intestines. Retroperitoneal fibrosis

is a disease where a fibrous process envelops either one but typically

both ureters which causes compression and subsequent kidney obstruction. Several

medications are known to cause RPF but most commonly, the process is

idiopathic meaning that no definitive cause can be identified.

Patients

with RPF can sometimes be managed with ureteral stents to relieve the

obstruction, but in many cases, the fibrotic process is strong enough to

compress stents and the obstruction recurs. In these cases, a nephrostomy tube can be placed or the patient can undergo a procedure called ureterolysis. During

an ureterolysis, which can be performed either open or

laparoscopically, the ureter is released from the fibrotic process and

then either placed inside the peritoneal cavity or wrapped with a

protective layer or fat called omentum, to help prevent the fibrotic

process from recurring. During this procedure, a biopsy of the fibrous tissue is made to confirm the diagnosis and exclude cancer.

Congenital Ureteral Anomalies:

In

addition to ureteropelvic junction obstruction, there are several other

causes of ureteral obstruction that may be due to congenital

abnormalities. In some patients, the ureter inserts into an abnormal location (ectopic) in the bladder which may lead to obstruction. This

condition is more common in patients with a duplicated collecting

system where there are two ureters and two collecting systems

originating in the same kidney, and one of the ureters often is ectopic

and leads to obstruction.

This

condition may be treated by reimplanting the obstructed ureter into

another location in the bladder or by attaching the obstructed ureter

into the non-obstructed ureter from the same kidney

(uretero-ureterostomy). If there is long-standing

obstruction, the portion of the kidney drained by the obstructed ureter

may lose function and the best treatment may be to remove this portion

of the kidney along with its obstructed ureter, leaving the remaining

viable portion of the kidney intact.

A typical ureter lies above the large vein running above the spine called the inferior vena cava (IVC). However,

some patients have what is known as a retrocaval or circumcaval ureter

where the ureter courses behind this large vein and may lead to

obstruction. This is managed by dividing the ureter and then re-connecting it in front of (anterior) the IVC.

Another congenital condition that may cause urinary tract obstruction is an ureterocele. This

is a cystic outpouching of the ureter as it enters the bladder and

forms a small balloon like sac in the bladder which may obstruct the

flow of urine from the affected kidney, and if large enough, may even

obstruct the flow of urine from the opposite kidney. The

ureterocele can be punctured endoscopically (through a tube) or, in

larger cases, may be excised and the ureter reimplanted into a different

location in the bladder.

Neurogenic Bladder:

A normal bladder stores urine at low pressures until it gets close to its capacity, often around 400cc. In

many patients with neurologic diseases such as a spinal cord injury,

the bladder has decreased compliance meaning that the pressure in the

bladder increases significantly as it fills with urine (bladder becomes

stiff). This high pressure can cause the urine flowing

down the ureters from the kidneys to get backed up resulting in

obstruction and hydronephrosis (swelling of the kidneys) in the kidneys. Over time, this can lead to deterioration of renal function.

The

treatment of this process is aimed at decreasing the pressure in the

bladder which can be accomplished with various medications, as well as

keeping the bladder relatively empty by having the patients urinate

frequently. In many cases, patients are unable to urinate

normally so a catheter can be left in the bladder, or a catheter may be

placed into the bladder to empty the urine several times daily; this is

referred to as clean intermittent catheterization (CIC). The

goal of CIC in most patients with a neurogenic bladder should be to

catheterize as frequently as necessary to keep the total volume to 400cc

or less as this will prevent infections and preserve renal function. In

some severe cases, when these more conservative methods fail, the urine

must be diverted by creating a low pressure urinary diversion with a

loop of intestine draining into a bag on the skin which is known as an

ileal conduit. With proper bladder drainage and medications, many patients with neurogenic bladders are able to preserve their renal function.

Obstruction from Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH):

As

men get older, the prostate typically becomes larger and may cause

bothersome urinary symptoms such as frequency, urgency, and incomplete

bladder emptying. In some cases, the prostate may become

so obstructive that the bladder is always full and urine only leaks out

in small amounts when the bladder capacity is exceeded, a condition

known as overflow incontinence. When this occurs, the

urine does not drain normally from the kidneys as there is nowhere for

it to drain so hydronephrosis may occur. If left untreated, this may

lead to deterioration of renal function.

The

initial treatment for urinary obstruction due to prostatic enlargement

is to place a catheter into the bladder to allow the urinary system to

decompress. Once this is accomplished, there are multiple

options for managing BPH and these are discussed in detail in the benign

prostatic hyperplasia Knol.

Urethral Stricture Disease:

The urethra is the tube where the urine passes on its way out of the body from the bladder. Narrowing

or stricturing of the urethra may occur as a result of a congenital

defect, infection (typically gonorrhea or chlamydia), or trauma such as a

straddle injury (e.g., falling onto the crossbar of a bicycle). In

rare cases, if the stricture is severe, the urine may not be able to

pass through the urethra and the bladder becomes chronically filled,

which may subsequently lead to hydronephrosis.

Urethral

strictures may be treated by dilation, incision with a small endoscopic

knife (direct visual internal urethrotomy), or with a larger

reconstructive operation known as an urethroplasty where the narrowed

segment is excised and the two healthy ends of the urethra are

re-attached. In some cases of long urethral strictures,

some type of tissue flap may be needed to help bridge the gap to allow

for reconstruction. In addition to strictures of the more

proximal urethra, sometimes there is obstruction at the end of the

urethra which is known as urethra meatal stenosis. This

can be corrected either by dilating the urethral opening or

occasionally, the natural opening may need to be widened surgically to

allow better urine flow. In men, the foreskin can also

become obstructive, either from congenital tightness or scarring from

infection, a condition known as phimosis. Typically, a circumcision is necessary to treat a phimosis severe enough to cause difficulty passing the urine.

Posterior Urethral Valves:

Posterior

urethral valves (PUV) are a congenital anatomic defect of the male

urethra that may lead to severe urethral obstruction in infants and

cause bladder distention, and hydronephrosis. The valves are small flaps of tissue that in normal males regress into non-obstructing urethral folds. PUV

are often diagnosed on prenatal ultrasonography by a markedly dilated

bladder, elongated posterior urethra, and hydronephrosis in both

kidneys.

The obstruction is initially

relieved by placement of a catheter into the bladder and the valves can

subsequently be incised endoscopically. In some cases,

the bladder is sewn directly to a small opening in the skin

(vesicostomy) to allow for drainage until the child undergoes a

definitive valve ablation. As this is a congenital

condition, even prompt intervention post-natally may be unable to

reverse any pre-existing damage to the kidneys.

Conclusions:

There are many different types of urinary tract obstructions. These

obstructions may result in swelling (hydronephrosis) of one or both

kidneys, which if left untreated may lead to deterioration of renal

function. The treatment of the obstruction may range from

simple observation – as in the case of a small kidney stone – or may

require major reconstructive surgery. It is important to have a discussion with your urologist regarding the risks and benefits of all the treatment options. The

bottom line is that all efforts should be made to preserve kidney

function to avoid the need for dialysis or renal transplantation.