Author: Dr Brent Yanke Urologist West Orange New Jersey 2008-07-28

Hematuria: Blood in the Urine

KIDNEY ANATOMY AND FUNCTION

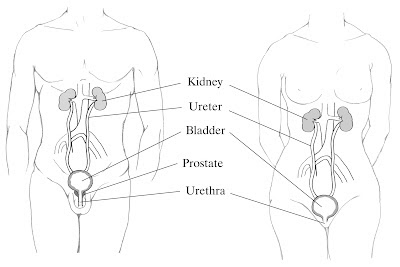

The

kidneys are organs responsible for cleansing the blood of waste. Many

byproducts of metabolic processes in the body build up in the

bloodstream. A microscopic tubular system within the kidney filters the

blood and removes these byproducts before they can accumulate to

dangerous levels. Once blood enters the kidney, it is transported to a

collection of small capillary vessels, called the glomerulus. As the

blood passes through the glomerulus, the filtrated waste shifts to

Bowman’s capsule, a pouch that surrounds the glomerulus and starts the

tubular system. Kidney tissue is separated into two layers: the outer

cortex and the inner medulla. Once the filtered waste passes through

these layers, it reaches the renal papillae which project into the renal

pelvis, an open space in the core of the kidney, where the urine

collects. The urine then drains from the renal pelvis into the ureter

and finally into the bladder. The kidneys and ureters comprise the upper

urinary tract, while the bladder and urethra comprise the lower urinary

tract (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Anatomic Representation of the Male (Left) and Female (Right) Urinary Tract

Courtesy of National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

WHAT IS HEMATURIA AND HOW IS IT CLASSIFIED?

Hematuria is the presence of blood in the urine. Studies have found it in 2.5% to 21% of the general population.1 When the blood is visible to the patient, it is referred to as gross hematuria. More often, blood is found on routine testing and is visible only by microscopic analysis; this is termed microscopic hematuria.

The American Urological Association defines microscopic hematuria as

the presence of three or more red blood cells per high-power field on

microscopic evaluation from two out of three urine specimens.2

As

discussed below, the presence of microscopic hematuria can prompt

various degrees of evaluation based on the clinical situation, ranging

from complete examination to none at all. However, gross hematuria

should always lead to a full urologic work-up due the higher risk of

malignancy (cancer). Several large studies have shown much higher rates

of malignancy with gross hematuria (18% to 25%) compared with

microscopic hematuria (3% to 5%).3,4

ARE THERE SYMPTOMS ASSOCIATED WITH HEMATURIA?

The

majority of patients who come to the doctor with hematuria have no

accompanying symptoms. However, certain associated symptoms can suggest a

particular medical condition.

Pain is frequently found with

microscopic and gross hematuria. Both pain and hematuria can be caused

by a common underlying source, or the pain can be a direct result of the

hematuria itself. Often the location and nature of the pain can give a

clue to the cause. Sharp flank or lower abdominal pain suggests that the

ureter is blocked, called ureteral obstruction. This may be caused by a

passing stone with resulting pain and hematuria following ureteral

trauma. Likewise, clots formed from bleeding in the upper urinary tract

can cause similar pain when traveling through the ureter. These clots

tend to be thin and wormlike, while clots formed in the bladder and

prostatic urethra are more likely to be larger and appear as nonspecific

clumps.5 Pain associated with urination may be more

indicative of a bladder infection, particularly when urinary frequency

and urgency are present as well. While these infections tend to cause

microscopic hematuria, gross hematuria is also common.

In men

with an enlarged prostate, called benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH),

hematuria can be present with symptoms of bladder obstruction. These

patients can have slow urinary stream, difficulty initiating urination,

and urinary frequency and urgency at night. While the hematuria is

generally painless, the formation of clots in the bladder and prostate

can lead to complete obstruction and an inability to urinate with

resulting discomfort.

It is

important for any patient with urinary symptoms and hematuria to be

evaluated for a bladder tumor. These tumors can cause urinary urgency

and frequency and may mimic the above benign conditions.

THE CAUSES OF HEMATURIA

The

initial assessment of hematuria centers on establishing the potential

sources. Namely, it must be determined whether the cause is of

glomerular origin or nonglomerular origin. Microscopic urinalysis

provides essential information in differentiating these.

The urine specimen of patients with glomerular disease often exhibits one or more of the following:

- Proteinuria – This is the presence of protein in the urine. Normally, the glomeruli prevent a significant amount of protein from entering the forming urine. Urine protein levels higher than 1,000 mg for a 24-hour period are highly suggest glomerular disease. Even considerable amounts of gross hematuria from nonglomerular causes do not raise protein concentrations to this level.5

- Red blood cell casts – Casts are cells seen clumped together in the urinalysis. The source of casts is from the glomeruli of the kidney. Blood cells are normally prevented from passing through the glomeruli into the renal tubular system. However, when glomerular damage is present, blood cells can pass into the tubules where they cluster together to form casts. Although casts are generally not seen in nonglomerular hematuria, the absence of casts does not exclude glomerular sources as up to 20% of these patients can have hematuria without casts.6

- Red blood cell shape – Normal red blood cells are round with similar size and shape. This is typical of nonglomerular bleeding. However, bleeding of glomerular origin leads to irregularly shaped red blood cells of varying size.7-9

CAUSES OF GLOMERULAR HEMATURIA

Many

diseases can affect the renal glomerulus leading to hematuria. Common

causes are listed below. Although learning that blood is present in the

urine can be an upsetting experience, a majority of the glomerular

causes actually are rather harmless and have no major long-term

consequences.

IgA Nephropathy (Berger’s Disease)

- The most common diagnosis in patents with glomerular hematuria representing approximately 30% of all cases.6

- Hematuria can be either gross or microscopic.

- More frequently diagnosed in younger patients and in men.

- Gross hematuria is more common in children, but hematuria is more likely to be microscopic with advancing age.10

- The disease can present as hematuria after an upper respiratory infection particularly in younger patients.

- It is diagnosed by renal biopsy.

- Most of these patients will encounter few, if any, long-term health concerns. However, in 5% to 25% of patients, the disease will progress.11 These patients will develop various degrees of renal failure along with worsening proteinuria and elevated blood pressure.

Familial Nephritis (Alport’s Syndrome)

- This accounts for roughly 10% of glomerular hematuria cases.6

- There is invariably gross hematuria.

- It is hereditary with multiple genetic mutations present.

- A strong family history of renal failure is present, often with multiple family members affected.

- Other associated symptoms include deafness and eye abnormalities.

Other Glomerulonephritis (GN) Syndromes

- Membranous GN – Patients undergo the following three clinical courses in roughly equal proportions: Resolution of the disease, continued disease but with stable kidney function, and renal failure.

- Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis – Approximately half progress to renal failure.

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus – This is an autoimmune disease that predominantly occurs in women. Almost any part of the body can be affected by the disease and its severity is extremely variable. The kidneys are involved in a majority of patients, but most have no symptoms and few progress to renal failure. Gross or microscopic hematuria can be seen and occasionally can be the first and only symptom.

- Poststreptococcal GN – Generally temporary with little risk of permanent injury, this can be seen in young patients who have had a recent streptococcal upper respiratory infection.

CAUSES OF NONGLOMERULAR HEMATURIA

Nonglomerular

causes of hematuria can be due to a large array of processes throughout

the upper and lower urinary tract. Diseases such as cancer, infection,

and stones all need to be considered when evaluating for urological

sources of hematuria. The more notable causes are listed by organ below.

Kidney

Kidney Cancer

Historically,

the common presentation of kidney cancer involved one or more of the

triad of gross hematuria, flank pain, and a flank mass. However,

hematuria rarely is seen as an early symptom in modern times. This is

due to the widespread use of radiologic imaging, which has allowed these

cancers to be found much earlier before hematuria has developed.

However, some renal cancers may still be diagnosed at an advanced stage.

Gross hematuria may be present when the tumor invades into the renal

pelvis and urinary collecting system, while microscopic hematuria may

result from invasion of the cancer into normal kidney tissue.

Urethelial Cancer of the Renal Pelvis

Urothelial

cancer of the renal pelvis arises from the cells that line the renal

pelvis of the kidney where urine first collects. As is seen with renal

cancers, hematuria may be gross or microscopic.

Stones and Hypercalciuria

Stones

of any size can cause hematuria by traumatizing the urothelial lining

within the kidney (Figure 2). When the stones remain in the kidney, the

hematuria may not be associated with pain. Hematuria has also been

linked to hypercalciuria (elevated levels of calcium in the urine).12

These patients have a strong family history of stone disease and

treatment with thiazide diuretics generally leads to resolution of the

hematuria.

Figure 2. Endoscopic View of Bleeding Caused by a Renal Stone

Pyelonephritis

Infection

of the kidney, termed pyelonephritis, can often cause hematuria. This

should be suspected when the hematuria occurs in conjunction with back

pain, fevers, and chills. Treatment of the infection with antibiotics

will halt the hematuria.

Hereditary Renal Disease

- Cystic Disease – Adult polycystic kidney disease (APKD) and medullary sponge kidney (MSK) are inherited disorders where cysts, or pouches filled with fluid, form within the kidney. APKD invariably leads to renal failure while MSK does not. Hematuria is due to cysts that bleed into the collecting system.

- Papillary Necrosis – Papillae within the kidney die and shed into the renal pelvis and ureter causing hematuria and pain from obstruction. This can be seen in sickle cell disease, a hereditary disease seen in African-Americans that causes the body’s red blood cells to be abnormal. It has also been associated with diabetes and ingestion of Phenacetin, an analgesic medication not commonly used today.

Vascular Disease

- Arteriovenous Fistulas – These are abnormal collections of blood vessels that frequently bleed and can be a source of persistent painless hematuria. Although more common in the kidney, they can occur at any location along the urinary tract.

- Renal Artery and Vein Thrombosis – A thrombosis is a clot that forms within a blood vessel. When this occurs in the renal artery, a portion of the kidney may infarct (die) leading to pain and hematuria. A thrombosis in the renal vein reduces the ability of blood to drain from the kidney.

Ureter

Stones

As

stones pass from the kidney into the ureter, they will frequently cause

pain along with hematuria. The hematuria may be microscopic or gross

and is a result of trauma to the urothelial lining of the ureter as the

stone descends. There may also be urinary symptoms such as frequency and

urgency once the stone reaches the last part of the ureter and passes

into the bladder.

Ureteral Cancer

Tumors

of the ureter may present with hematuria as well as pain and renal

failure due to obstruction of the ureter. These tumors can present with a

jet of blood entering the bladder from the involved ureter.

Bladder

Stones

Aside

from stones that have passed into the bladder from the upper urinary

tract, hematuria can be caused by stones that have formed within the

bladder. This is typically seen in patients with benign prostatic

hypertrophy (BPH) where an enlarged prostate obstructs the bladder. As a

result, the bladder may be unable to empty urine completely, and

crystals within the urine form stones. It is common to have multiple

stones in this setting, with some growing larger than a golf ball.

Bladder Cancer

Tumors

of the bladder almost always present with hematuria. Larger tumors may

bleed profusely, causing the urine to turn deep red and resulting in

clot formation (Figure 3). The clots may be rather large and fill the

bladder. When this occurs, the clots may obstruct the bladder, and the

patient may have pain and an inability to urinate.

Figure 3. Endoscopic View of Bleeding from a Bladder Tumor

Cystitis

Common

causes of cystitis (bladder inflammation) are infection and radiation.

Microscopic analysis of the urine during bladder infections will show

red blood cells along with white blood cells and possibly bacteria. The

patient typically will suffer from painful urination as well as urinary

frequency and urgency. Radiation cystitis can be seen in patients who

have received previous pelvic radiation. This is typically observed

after radiation treatment for prostate cancer. The bleeding can be quite

obvious and difficult to treat.

Prostate

Prostate Cancer

Due

to aggressive screening resulting in diagnosis at earlier stages,

nowadays hematuria is not commonly seen with prostate cancer. Before

modern screening, gross hematuria was quite common as prostate cancer

was often discovered at advanced stages.

BPH

While

the normal prostate has a high concentration of blood vessels, a

prostate with BPH has a significant increase in the density of blood

vessels.13 As a result, patients with BPH have a greater risk

of gross hematuria that can be frequent and, in some cases, severe

enough to cause clot formation and urinary retention.

Prostatitis

Hematuria

in the setting of prostate infection (prostatitis) will often occur

with a tender prostate on examination and worsening urinary symptoms.

Other Sources of Hematuria

Trauma

Injury

at any point along the urinary tract can cause hematuria. This can be

due to unplanned trauma, such as renal damage from a stab wound or

urethral injury from catheter insertion, or secondary to a procedure

such as laser surgery for stone disease.

Exercise-induced Hematuria

Hematuria

can be seen with strenuous exercise. It generally occurs with exercise

of longer duration and greater intensity. Once the activity is over, the

process resolves and has no long-term consequences.

Anticoagulation

Substantial

gross hematuria can be seen in patients taking medications that “thin

the blood” such as warfarin and heparin. However, the therapy itself

does not increase the risk for hematuria, unless levels of the

medication are well above therapeutic levels. Rather, anticoagulation

leading to hematuria uncovers urologic disease already present. One

study found urinary tract disease in 30% of patients on anticoagulation

therapy evaluated for hematuria.14 Importantly, the hematuria cleared in more than 90% of the patients after treatment.

EVALUATION OF PATIENTS WITH HEMATURIA

The

assessment of any patient with hematuria starts with a careful history

and physical examination. Identifying any family syndromes such as

sickle cell disease or cystic diseases of the kidney is an important

first step. It is also important to find out if the patient has any

other predisposing factors such as previous kidney stones or a history

of BPH. Hematuria in women during menstruation may be a contaminant, and

urinalysis should be repeated in between cycles.

Initial

laboratory tests consist of microscopic urinalysis and measurement of

serum creatinine (a blood test used to measure kidney function). The

urine should be analyzed for number and shape of red blood cells as well

as presence of white blood cells, bacteria, protein, and crystals. As

mentioned previously, abnormal red cells, casts, and significant

proteinuria indicate glomerular disease. White blood cells and bacteria

suggest infection, while crystals may be a result of stone disease. The

serum creatinine level is an indication of renal function, and an

elevated level in the face of glomerular disease requires prompt

referral to a nephrologist (physician who specializes in kidney

diseases).

GROSS HEMATURIA

Visible hematuria generally requires a full evaluation of the upper and lower urinary tracts.

Urine Cytology

Cytology

examines urine for cancerous cells of the urothelium (lining of the

urinary tract). The test has greater sensitivity for bladder cancer than

for cancers of the renal pelvis or ureter.

Radiologic Evaluation

Imaging

allows for the identification of renal tumors, stones, and significant

infections. Conventional radiologic evaluation was by intravenous

pyelogram (IVP). During this study, contrast dye is injected into a

vein, and a series of X-rays are taken as the dye is excreted by the

kidneys. Computerized tomography (CT) urography has largely replaced the

IVP. It provides a more detailed view of the upper urinary tract. For

patients with allergy to contrast dye or poor renal function, an

ultrasound of the kidneys, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or a

retrograde pyelogram where dye is safely injected into the ureters and

kidneys can be performed.

Cystoscopy

Unfortunately,

radiologic imaging cannot identify small bladder tumors. Therefore, the

bladder is examined directly with a telescope attached to a camera

(cystoscopy). The smallest of tumors can be seen, as can stones or

prostatic bleeding. The entrance of each ureter into the bladder (the

ureteral orifices) is also examined, and in some upper tract disease,

blood can be seen spurting into the bladder (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Endoscopic View of Blood Entering the Bladder from the Right Ureteral Orifice

MICROSCOPIC HEMATURIA

Not

all patients with microscopic hematuria without symptoms need a

complete urologic assessment like that performed with gross hematuria.

However, patients with a higher risk for disease should undergo a full

urologic workup. These risks are as follows:2

- Smoking history

- History of gross hematuria

- History or urologic disease such as bladder cancer or stones

- History of bothersome urinary symptoms such as frequency and urgency

- Age older than 40 years

- Studies have shown no benefit to the screening of patients younger than 40 years15

- The risk of bladder cancer and other pathology increases with age16

- History of pelvic irradiation

- Occupational exposure to cancer-causing chemicals

- Abuse of pain medications (such as the anti-inflammatory aspirin, ketorolac, and ibuprofen)

- Previous urinary tract infections

If

none of the risk factors listed above are present, then radiologic

evaluation can be accompanied by urine cytology or cystoscopy. However,

if the cytology is suspicious, then a cystoscopy must be performed.

Patients

suspected of having benign transient microscopic hematuria should have

repeat urinalysis 48 hours after the offending activity is stopped.2

Examples include exercise-induced hematuria, menstruation, and trauma.

If the hematuria is still present, then a complete work-up is needed.

NEGATIVE WORK-UP

Some studies have shown that 10% or more of patients will have no abnormality found.1 However, disease can develop later and follow-up should be performed. This can consist of repeat urinalysis, cytology, and blood pressure measurement at 6, 12, 24 and 36 months.2 If any findings are suspicious then a complete work-up should be repeated. If the patient remains symptom free, then no further evaluation is needed.CONCLUSION

There are many causes of hematuria and although serious pathology may be associated more with gross rather than microscopic hematuria, any documented case should be properly evaluated. While the appearance of blood in the urine can be quite alarming, many of the causes are quite benign and treatable.ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

National Cancer Institute – www.cancer.gov

American Urological Association – www.urologyhealth.org

American Cancer Society – www.cancer.org

National Kidney Foundation – www.kidney.org

National Institutes of Health – www.nih.gov

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases – www.niddk.nih.gov

REFERENCES

1. “Hematuria.” UrologyHealth.org. Accessed 10 February 2008.

2. Grossfield

GD, Wolf JS, Litwin MS, Hricak H, Shuler CL, Agerter DC, Carroll PR.

Asymptomatic microscopic hematuria in adults: summary of the AUA best

practice policy recommendations. Am Fam Physician. 2001; 63: 1145-54.

3. Edwards

TJ, Dickinson AJ, Natale S, Gosling J, McGrath JS. A prospective

analysis of the diagnostic yield resulting from the attendance of 4020

patients at a protocol-driven haematuria clinic. BJU Int. 2006; 97: 301-5.

4. Alishahi

S, Byrne D, Goodman CM, Baxby K. Haematuria investigation based on a

standard protocol: emphasis on the diagnosis of urological malignancy. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 2002; 47: 422-7.

5. Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, Partin AW, Peters CA eds. Campbell’s Urology, 9th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders.

6. Fassett RG, Horgan BA, Mathew TH. Detection of glomerular bleeding by phase-contrast microscopy. Lancet. 1982; 26: 1432-4.

7. Schramek

P, Schuster FX, Georgopoulos M, Porpaczy P, Maier M. Value of urinary

erythrocyte morphology in assessment of symptomless microhaematuria. Lancet. 1989; 2: 1316-9.

8. Fassett RG, Horgan B, Gove D, Mathew TH. Scanning electron microscopy of glomerular and non glomerular red blood cells. Clin Nephrol. 1983; 20: 11-6.

9. Pollock

C, Liu PL, Gyory AZ, Grigg R, Gallery ED, Caterson R, Ibels L, Mahony

J, Waugh D. Dysmorphism of urinary red blood cells--value in diagnosis. Kidney Int. 1989; 36: 1045-9.

10. D’Amico. Clinical features and natural history in adults with IgA nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis. 1988; 12: 353-7.

11. Coppo R, D’Amico G. Factors predicting progression of IgA nephropathies. J Nephrol. 2005; 18: 503-12.

12. Praga

M, Alegre R, Hernandez E, Morales E, Dominguez-Gil B, Carreno A, Andres

A. Familial microscopic hematuria caused by hypercalciuria and

hyperuricosuria. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000; 35: 141-5.

13. Foley SJ, Bailey DM. Microvessel density in prostatic hyperplasia. BJU Int. 2000: 85: 70-3.

14. Van Savage JG, Fried FA. Anticoagulant associated hematuria: a prospective study. J Urol. 1995: 153: 1594-6.

15. Froom P, Ribak J, Benbassat J. Significance of microhaematuria in young adults. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1984; 288: 20-2.

16. Messing EM, Young TB, Hunt VB, Roecker EB, Vaillancourt AM, Hisgen WJ, Greenberg EB, Kuglitsch ME, Wegenke JD. Home screening for hematuria: results of a multiclinic study. J Urol. 1992; 148: 189-92.