Author: Dr John Maa University of California San Francisco 2008-07-29

Bariatric surgery: Overview on Weight Loss Surgery

Bariatric surgery is a term for operations to help promote weight loss.

Bariatric surgery: Overview on Weight Loss Surgery

Bariatric surgery is a term for operations to help promote weight loss.

Search terms: obese, bariatric surgery, weight loss, surgery, gastric bypass, stomach stapling, overweight, laparoscopic banding

Introduction:

Obesity is the condition in which fatty tissue stores are excessive. Obesity is associated with a number of co-morbid illnesses and an increased risk of premature death. The term overweight means that an individual has more body fat than is optimal. Morbid obesity is defined as being 100 lbs or more over ideal body weight or having a body mass index (BMI) of 40 or higher. BMI is a measure of body fat based on height and weight.

The

dramatic increase in obesity among Americans has become a critical

public health problem, especially among youths. Obesity is the second

leading cause of preventable death in the US. The

prevalence of obesity in America has been increasing from year-to-year

as is illustrated in the Department of Health and Human Services Center

for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) U.S. Animated Obesity Map

(Figure 1). The number of overweight and obese Americans has increased almost continuously since 1960.

A number of environmental factors are associated with the development of obesity, including socioeconomic

status, race (more pronounced among Hispanic and Black populations),

and region of residence (highest in the Southeastern US). Recently,

the CDC report "Obesity Among Adults in the United States -- No Change

Since 2003-2004," found that obesity prevalence has plateaued, but

levels are still high –- at 34% of U.S. adults aged 20 and over.[i] An estimated 100 million adults in the United States are overweight or obese.

Central obesity

is also known as "apple-shaped" or "masculine" obesity, and occurs when

the primary deposits of fat are around the abdomen and upper body. Central obesity is associated with greater morbidity than peripheral obesity (fatty deposition on extremities and thighs), due to the increased metabolism of visceral fat. Central obesity is a leading risk factor for the development of the metabolic syndrome,

which is a combination of medical disorders that increases the risks of

developing cardiovascular disease and diabetes. This results from

elevated blood sugars and cholesterol, increased insulin secretion,

hypertension, and atherosclerosis.

What are the causes of morbid obesity?

The precise causes of morbid obesity are unknown, but are postulated to include the following:

Genetics:

Obesity can often be traced to genes, and abnormalities of neural or

hormonal transmitters to the hypothalamus or satiety center (the

neurologic center that controls the sensation of fullness) can cause

disruption of normal appetite tendencies.

Psychology: Psychologically induced oral dependency drives and emotional problems, and depression can lead to obesity.

Lifestyle:

Poor diet and low levels of daily activity are contributors to obesity.

Morbidly obese adults have been found to have a lower basal energy

expenditure.

What health conditions are related to being obese?

Obesity

is associated with many health consequences, such as high blood

pressure, respiratory and heart disease, lipid problems, and diabetes,

and has been implicated in some types of cancers. Obesity

can contribute to cardiac enlargement and impaired heart function,

irregular heart beat, and respiratory complications from the increased

weight of the chest wall. These factors can predispose patients to the development of coronary and cerebrovascular disease/stroke.

The list of co-morbid diseases include:

1) adult onset diabetes

2) sleep apnea

3) osteoarthritis

3) osteoarthritis

4) cancer

5) fatty liver disease

6) hypertension

7) high cholesterol and triglycerides (fat levels in the blood)

8) coronary artery disease

9) stroke

10) heart failure

11) venous thrombosis (blood clots) and venous stasis ulcers

12) pulmonary embolism (blood clots that travel to the lung)

13) heartburn

14) depression[ii]

Because of these associated medical problems, being obese can result in a shortened life span. One study suggested that the risk of death increased by 20- 40% among overweight persons, and by 200-300% among obese persons.[iii]

The term morbid obesity indicates the life-threatening seriousness of the condition. The death rate is greater for morbidly obese people than for people of average weight. Premature

death is much more common, and there is a 12-fold excess mortality in

morbidly obese men in the 25 to 34 year age group. Massively obese

patients—those who weigh more than twice the ideal weight – suffer

physical, emotional, social, and economic hardships.

What is body mass index?

The body mass index (BMI) is a standard way to define overweight, obesity, and morbid obesity, and is a measure of body fat based on height and weight that applies to both adult men and women. The average BMI in American society is 25. A BMI of 25 or more is considered overweight, and 30 or more to be obese. Morbid obesity is defined as either a) body weight 100 lbs over ideal, or 2) a BMI over 40. Surgical

intervention is currently indicated for patients with a BMI over 40, or

a BMI over 35 with recognized comorbid conditions.

The BMI is calculated as:

In International units:

BMI = Weight in KILOGRAMS /(Height in METERS)2

In English units:

BMI = Weight in POUNDS x 703 /(Height in INCHES)2

A BMI calculator can be found at http://www.nhlbisupport.com/bmi/

The current consensus definitions establish the following values:[iv]

- A BMI less than 18.5 is considered underweight

- A BMI of 18.5–24.9 is considered normal weight

- A BMI of 25.0–29.9 is considered overweight

- A BMI of 30.0–39.9 is considered obese

- A BMI of 40.0 or higher is considered severely (or morbidly) obese

- A BMI of 35.0 or higher in the presence of at least one other significant comorbidity (diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, hypertension, sleep apnea, or degenerative joint disease) is also classified as morbid obesity.[v]

The 5th and 6th BMI categories above are also the criteria for weight loss surgery.

Consideration

of a patient's body shape, height, and muscularity should also be taken

into account, since muscle is more dense than fat. If one is muscular, then other means of determining body fat should be employed. A

report in the Journal of the American Medical Association demonstrated

that 97% of players in the National Football League are technically

overweight and more than 50% are obese.[vi]

Why Bariatric Surgery (Weight Loss Surgery)?

For people who are overweight or obese, but not morbidly obese, diet and exercise are the safest and best way to reduce weight and reduce health risks. If you are just overweight, the risk of bariatric surgery outweighs the risk of premature death and future medical problems.

However, for

men who are less than 100 pounds overweight and women who are less than

80 pounds overweight, weight loss surgery has been shown to be the most

effective treatment.[vii] If

you are morbidly obese, or obese with at least one co-morbidity, over

your lifetime you are at higher risk of dying prematurely or suffering

from worsening health problems, and the risk of bariatric surgery is

justified

Thus

a gastric bypass is offered to reduce your caloric intake and have been

unable to achieve the desired weight through diet and exercise. Gastric

bypass surgery can improve the quality of life not only because of an

improvement in appearance and an increase in mobility, but because it

can also reduce the severity of health problems from which overweight

people are prone to suffer.

What are the indications for bariatric surgery?

Obesity surgery was throughly evaluated by a consensus panel assembled by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) in 1990. The

consensus statement issued by this multidisciplinary panel of surgeons,

internists, and public health specialists is the major defining

standard for the care for obesity surgery.

The NIH created the following guidelines for bariatric surgery:

- A BMI of 40.0 or higher is considered severely (or morbidly) obese

- A BMI of 35.0 or higher in the presence of at least one other significant co-morbidity is also classified as morbid obesity.[viii]

The

panel also reviewed the existing data at that time and concluded that

only the vertical banded gastroplasty and Roux-en-y gastric bypass could

be recommended. These surgical approaches are discussed below.

Are there any alternatives to bariatric surgery?

The

standard approach to therapy for obesity begins with reducing diets and

medical counseling, but unfortunately these measures are often

unsuccessful in patients with severe obesity. The weight that is rapidly

lost is often quickly regained.

Non-surgical options for the treatment of morbid obesity include

1) diet modification

2) exercise programs

3) medications and

4) social support programs

To

date, non-surgical treatments have not been very effective in treating

obesity, regardless of the approach used, with high rates of recurrence,

up to 90%.[ix] No

dietary approach has achieved uniform long-term success for the

morbidly obese—many can lose weight temporarily but it then regain. There are currently no effective pharmacologic agents to treat obesity. Surgery

is currently accepted as the treatment approach producing the greatest

and longest-lasting success in achieving weight loss.

How safe is bariatric surgery?

Bariatric surgery is often portrayed as a high risk procedure. While

the surgery is, indeed, more risky than many other operations, much of

the risk relates to the patient’s obesity rather than to the actual

operation itself. Nonetheless, surgery has inherent risks including significant early and late morbidity and perioperative mortality. An

extensive review of 361 bariatric surgery studies including over 85,000

patients found that the total mortality within the first 30 days of

surgery was 0.28%, and the total mortality during the period from 30

days to 2 years was 0.35%.[x]

Surgery for obesity is more effective than medical management, producing greater weight loss. A trial 80 adults with mild to moderate obesity (BMI 30-35 kg/m2)

randomized patients to either adjustable gastric banding or an

intensive medical (non-surgical) program and found that at 2 years, the

surgical group had lost 87.2% of excess weight, while the non-surgical group lost only 21.6%.[xi] as well as improvements in quality of life and co-morbidities have also be found. 12 The continued weight loss after gastric bypass has been documented to extend for as long as 10 years after initial operation. [xii] Surgery was found to be more effective than non-surgical weight loss in terms of reducing both weight and health risks.[xiii]

Is bariatric surgery appropriate for children and teenagers?

The

number of U.S. children having obesity surgery has increased rapidly in

recent years, at a pace that could result in more than 1,000 such

operations in 2008. The procedure remains far more common

in adults, but preliminary data suggests it may be slightly less risky

in teens, according to an analysis of data on 12- to 19-year-olds who

had obesity surgery from 1996 through 2003. Adolescents

should be strongly encouraged to attempt dietary and exercise

interventions first, and bariatric surgery should only be undertaken

after careful consideration by the patient, family, physician, and

medical center.

What steps must be undertaken before I can have bariatric surgery?

Before

bariatric surgery is offered, a potential patient must undergo an

extensive evaluation by a multidisciplinary team of providers to address

all aspects of the complex medical, surgical, psychological, and nutritional issues.

Potential

patients must commit to compliance with the diets postoperatively, and

comply with lifelong follow-up for potential ongoing medical conditions. Marked

anemia can develop after bariatric surgery if vitamin supplementation

is inadequate, and often results from the failure of coupling of vitamin

B12 to intrinsic factor or insufficient stores of folate.

What additional procedures might be necessary in conjunction with bariatric surgery?

Additional surgical procedures are sometimes recommended at the same time, or after, bariatric surgery. Approximately

30- 40% of patients who undergo gastric bypass will subsequently form

gallstones, thus many surgeons recommend removal of the gallbladder at

the time of bariatric surgery.

If

excess fat or skin is localized in an area, a simultaneous or staged

panniculectomy (liposuction) may be performed- especially for those

patients who develop a hernia in their incision after marked weight

loss.

How long does it take to lose weight?

Most

patients observe the majority of their weight loss within one year and

achieve a stable weight by the end of the second year. Their

weight loss plateaus once their caloric intake and caloric expenditure

are balanced. On average, there is a reported loss of one half to two

thirds of excess weight within 1 to 1.5 years. This

weight loss completely corrects insulin dependent diabetes in most

cases, and most patients no longer require insulin after bariatric

surgery. Many patients have resolution of their headaches

from a reduction of cerebrospinal fluid pressure elevation, and many

cases of obstructive sleep apnea and gastroesophageal reflux also

resolve.

History of Bariatric Surgical Therapy:

The

first operations to control obesity were small bowel bypasses, which

rely on malabsorption alone – that is, surgically changing the stomach’s

anatomy to selectively prevent it from absorbing nutrients. The first

operation for obesity that gained widespread acceptance—the jejunoileal bypass --

is no longer performed as it was associated with an unacceptably high

rate of liver failure (in up to 10% of patients), renal failure, and

metabolic complications. Many surgeons believe that all jejunoileal bypass procedures should be reversed to prevent cirrhosis, and conversion to one of the bypass procedures described below if weight loss is to be maintained.

Current Surgical Therapy:

The

modern era of gastric procedures for weight loss was based on the

observation that some patients who underwent stomach ulcer surgery lost

weight afterwards. In 1969, investigators reported the

results of weight loss following reduction of the stomach to the size of

a small pouch. This technique was simplified with the use of stapling

instruments.

Current surgical procedures for weight loss have three essential approaches:

(1) the restriction of food intake (restrictive procedures)

(2) anatomic modification of the gastrointestinal tract to create selective malabsorption (poor absorption) of nutrients (malabsorptive procedures)

(3) a combination of both restrictive and malabsorptive procedures

The two most popular current surgical procedures for weight loss include gastric bypass and adjustable gastric banding. Other operations that have been done include vertical banded gastroplasty and biliopancreatic diversion and duodenal switch

but are falling out of favor due to loss of effectiveness (vertical

banded gastroplasty) and a high incidence of complications

(biliopancreatic diversion and duodenal switch).

Gastric Bypass

A gastric bypass is an effective procedure that achieves weight loss by both restrictive and malabsorptive mechanisms. The Roux-en-Y gastric bypass has become popular over the past decade as it results in substantial weight loss, but the long-term physiologic consequences are still being evaluated closely through multicenter research studies. It is an irreversible procedure. In this procedure, a portion of the small intestine (Roux-en-Y loop) is joined with a small portion of the upper stomach to create a small pouch (approximately 15 mL volume). The remainder of the stomach, duodenum, and proximal jejunum are excluded from food contact. In the standard procedure, the digestive secretions from the bile duct system and pancreas enter the jejunum 40- 50 cm from the stomach, resulting in malabsorption.

To promote greater weight loss, the procedure can be modified as a long limb gastric bypass (100 to 150 cm from the stomach) and is often considered in the superobese (BMI > 50). The procedure is well tolerated by most patients and is effective in achieving weight loss.[ix] Laparoscopic gastric bypass requires a high level of technical skill not possessed by most general surgeons.

The Roux-en-Y bypass is more common and considered less complicated

than the biliopancreatic diversion bypass, since Roux-en-Y does not remove portions of the stomach.

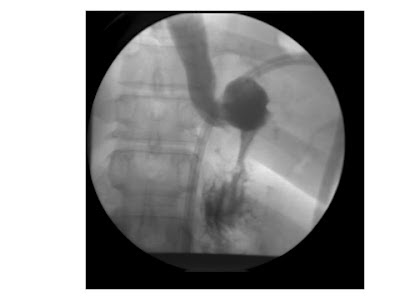

The

most feared complication after a gastric bypass is a postoperative

gastric leak with peritonitis resulting from bacterial escape into the

abdomen. It can be difficult to recognize due to the marked amount of

abdominal wall fatty tissue. Any signs of tachycardia,

fever, tachypnea, and leukocytosis should be carefully explored in a

postoperative gastric bypass patient. If suspicious, immediate reoperation should be performed.

Specific complications associated with gastric bypass include:

1) staple failure or disruption

2) anastomotic leaks and peritonitis

3) acute gastric dilatation

4) marginal ulceration

5) dumping syndrome (food moves too rapidly through the intestinal tract resulting in diarrhea)

6) stomal stenosis (narrowing of the connection between the stomach and intestines) which may require endoscopic dilation

Common postoperative complications such as wound infection, pulmonary embolism, hernia, and bowel obstruction are also observed.

Gastric Banding

Gastric

banding (also known as LAP BAND) is a popular alternative to gastric

bypass that is also reversible. It is commonly performed

laparoscopically and is less technically demanding than a laparoscopic

gastric bypass. Food intake is limited by the placement

of a constricting ring around the upper portion of the stomach, dividing

the stomach into a small portion above the band (a 5-15 mL pouch) and a

much larger portion below the band. The band can be

adjusted by inflation of a reservoir to allow gradual regulation of the

diameter of the stoma (the pouch outlet to the intestine). Laparoscopic

gastric banding has been shown to result in acceptable weight loss and

reductions in co-morbidities, but in some patients both the degree of

weight loss and reduction in co-morbid conditions are less than that

with gastric bypass.

Multi-center long-term results in the US are still being investigated.[xiv]

Since this is a restrictive procedure, gastric banding avoids the

problems associated with malabsorptive techniques such as malnutrition

and dumping syndrome. Specific LAP BAND complications include splenic or

esophageal injury, esophageal dilation, wound infection, band slippage

or erosion, reservoir deflation, persistent vomiting, and acid reflux.[xv]

Vertical Banded Gastroplasty

The vertical banded gastroplasty (VBG) is a restrictive procedure that limits the amount of food a patient is able to ingest. VBG is infrequently performed today due to the failure of many patients to achieve sustained weight loss,[xvi] and undesirable side effects such as heartburn and vomiting (reported in up to 38% of patients). In

this procedure, the stomach is divided by a stapler along the lesser

curvature to create a small pouch. A band or ring of silicone or

polypropylene mesh is placed through a hole in the stomach to limit the

size of the pouch outlet (stoma). Reasons for the failure

of this procedure may include dilation and enlargement of the gastric

pouch, stomal stenosis, staple line failure, and problems related to the

non-adjustable band.[xiv]

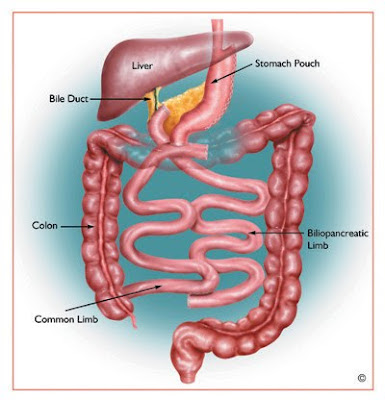

Biliopancreatic Diversion With and Without Duodenal Switch

The biliopancreatic diversion is a less common and more complex procedure than the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. It is less widely used, as there is a perceived greater risk of nutritional deficiencies. It can be performed both with and without the "duodenal switch." It

includes a malabsorptive procedure that involves removal of a portion

of the stomach and a long “Roux-en-Y” (where the small intestine is

re-fashioned into a “Y” shape). The small intestine is divided, and the

distal end (alimentary, or Roux-en-Y, limb) is connected to the gastric

remnant. The proximal (biliopancreatic) limb of intestine is connected

to the alimentary limb 50-100 cm from the ileocecal valve.

As

an alternative, the procedure may also be performed with a "duodenal

switch," in which the Roux limb is anastomosed to the duodenum rather

than the stomach, and a linear (sleeve) gastrectomy, in which a

significantly greater portion of the stomach is removed leaving a narrow

tube based on the lesser curvature of the stomach.

Weight

loss following biliopancreatic diversion is achieved by both

restriction and selective malabsorption of nutrients. Biliopancreatic

diversion may be the most effective in producing weight loss but is

technically difficult to perform, particularly laparoscopically, of

significantly higher risk, and may produce marked malnutrition and

vitamin deficiencies.[xvii] The advantage is that there is no blind intestinal limb.

Diagram:

Intra-Gastric Balloon

The

intent of the intra-gastric balloon is to create a sense of earlier

satiety by filling a portion of the stomach from within (a restrictive

procedure). It was developed to offer a nonsurgical and reversible approach to obesity control. However,

the intra-gastric balloon has been removed from the US market after

several publicized deaths resulted from obstruction secondary to the

passage of a partially digested intra-gastric balloon.

In

Europe and elsewhere in the world, the intra-gastric balloon is still

used temporarily, for periods of up to 6 months, as a “bridge” to bring a

severely obese patient down to a weight where they can undergo a

permanent bariatric operation with less risk. It must be removed within 6 months, otherwise digestion and resulting complications may occur. It

is therefore utilized primarily for mild cosmetic weight loss, and also

to help patients lose weight prior to one of the previously described

weight loss surgeries.

What if the initial procedure is unsuccessful?

A subset of patients will not achieve the desired weight loss postoperatively. Most patients who fail surgery do so from excessive calorie consumption relative to calories burned through activity. Attention

is first directed at determining whether the patients have continued to

ingest large amounts of sugar-containing beverages, or by preferential

ingestion of foods with a high caloric density.

After this has been excluded, patients can be considered as candidates for revisional surgery. However,

reoperation can be very difficult due to adhesions, scarring, and the

altered anatomy, and the attendant perioperative risks are much higher

than with the first procedure. Often the best results are

achieved by conversion to a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, though the use of a

modified partial biliopancreatic diversion can also be considered.

Newer Surgical Therapy and Endoscopic Therapy:

Vertical Sleeve Gastrectomy

Vertical gastrectomy (VG) is the

restrictive component of a more extensive mixed restrictive and

malabsorptive operation, the biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal

switch.[xviii] VG

was first performed as a distinct operation in 2001 with the intent to

remove approximately 90% of the stomach leaving a narrow tube or

“sleeve” which greatly reduces the stomach volume creating satiety, or

the sensation of fullness. The procedure minimizes the

complications of dumping and ulcer formation, but sometimes requires

completion of the second stage of the procedure to promote

malabsorption.

There

are currently 15 published reports in the surgical literature

describing short-term outcomes in 775 patients after sleeve gastrectomy.[xix] This

procedure has been shown to result in significant weight loss, with

excess weight loss ranging from 33% to 83%. Rates of resolution of

co-morbid conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and

sleep apnea within 12- 24 months are comparable to results of other

restrictive procedures.[xx] Similar

to other forms of gastroplasty, the perioperative risk for sleeve

gastrectomy appears to be relatively low, even in high-risk patients.

Published complication rates range from zero to 24% with an overall

reported mortality rate of 0.39%.[xviii]

Neuromodulation

The vagus nerve is involved in the control of digestion, intestinal motility, and feelings of fullness. Under

investigation is a surgically implanted unit that modulates the

electrical impulses of this nerve with the intent of slowing the rate of

stomach emptying to promote a sense of satiety. The initial weight loss has been inferior to established bariatric operations. Weight loss of 20 lbs at 20 weeks, and 36.1 lbs at 1 year, have been reported, but long-term data is pending.[xxi] The cost and replacement of the battery unit for this device has been recognized as a significant limitation.

Investigational Endoluminal or Endoscopic Therapies on the Horizon

Less

invasive approaches to surgery are being investigated, which utilize

endoscopes introduced through the mouth to achieve weight loss. Active areas of research involve approaches that include:

1) stapling from within the stomach to restrict the volume of the stomach

2)

lining the intestinal tract with a sheath to prevent contact between

food and digestive enzymes and thereby reduce absorption of food

3) ribbons, gels, or polymers which can fill the stomach to restrict volume

4) endoscopically implanted neuromodulation devices.

Diagrams:

EndoBarrier™ - http://www.gidynamics.com/endobarrier_technology

Summary:

For people who are overweight, diet and exercise are the safest way to achieve weight loss. For those who are morbidly obese or with significant co-morbidities, bariatric surgery is the most effective means to achieve weight loss to optimize health. Individuals considering bariatric surgery should discuss the risks and

possible benefits carefully with their physician, as surgery does

present associated risks and long-term consequences. Most bariatric surgeons

think that the operations represent only one part of the approach to

treating obesity and are most successful in conjunction with lifelong

behavioral and dietary changes.

Useful Web sites:

United States Animated Obesity Map showing state-by-state trends from 1985-2006.

American Society for Bariatric Surgery

http://www.asbs.org

http://www.asbs.org

American Society of Bariatric Physicians

Journal of the American Medical Association: Bariatric Surgery

American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery: The Story of Surgery for Obesity: A Brief History and Summary of Bariatric Surgery

Cleveland Clinic Health Information Center: Surgical Options for Severe Obesity

Medline Plus: Weight Loss Surgery

NIH (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases): Gastrointestinal Surgery for Severe Obesity

Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons: Morbid Obesity

American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery: Benefits of Bariatric Surgery

Related articles:

Santry HP, Gillen DL, Lauderdale DS. Trends in bariatric surgical procedures. JAMA 2005; 294: 1909-1917.

Zingmond DS, McGory ML, Ko CY. Hospitalization before and after gastric bypass surgery. JAMA 2005; 294: 1918-1924.

Zingmond DS, McGory ML, Ko CY. Hospitalization before and after gastric bypass surgery. JAMA 2005; 294: 1918-1924.

References:

[i] Ogden CL, Carroll MD, McDowell MA, Flegal KM. Obesity among adults in the United States – no statistically significant change since 2003-2004. NCHS Data Brief 1, November 2007. 8pp. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db01.pdf

[ii] Bray GA (2004). "Medical consequences of obesity". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 89 (6): 2583-9.

[iii] Adams KF, Schatzkin A, Harris TB, Kipnis V, Mouw T, Ballard-Barbash R, Holleenbeck A, Leitszmann MF. Overweight, Obesity, and Mortality in a Large Prospective Cohort of Persons 50 to 71 Years Old. NEJM 2006; 355: 763-778.

[iv] World

Health Organization Technical report series 894: "Obesity: preventing

and managing the global epidemic.". Geneva: World Health Organization,

2000.

[v] NIH National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases). Gastrointestinal surgery for severe obesity. Accessed 7th February 2008. http://win.niddk.nih.gov/publications/gastric.htm

[vi] Harp JB, Hecht L. Obesity in the National Football League. JAMA; 293: 1061-62.

[vii] Waseem T, Mogensen KM, Lautz DB, Robinson MK. Pathophysiology of obesity: why surgery remains the most effective treatment. Obes Surg 2007; 17(10): 1389=98.

[viii] NIH National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases). Gastrointestinal surgery for server obesity. Accessed 7th February 2008. http://win.niddk.nih.gov/publications/gastric.htm

[ix] The Practical Guide: Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. NIH Publication No. 00-4084 2000.

[x] Buchwald H, Estok R, Fahrbach K, Banel D, Sledge I. Trends in mortality in bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgery 2007; 142(4): 621-32.

[xi] O’Brien PE, Dixon JB, Laurie C, Skinner S, Proletto J, McNeill J, Strauss B, Marks S, Schachter L, Chapman L, Anderson M. Treatment

of mild to moderate obesity with laparoscopic adjustable gastric

banding or an intensive medical program: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2006; 144: 625-33.

[xii]

Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, Jensen MD, Pries W, Fahrbach K,

Schoelles K. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

JAMA 2004; 292: 1724-1737.

[xiii] Colquitt J, Clegg A, Loveman E, Royle P, Sidhu MK. Surgery for morbid obesity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; 4: CD003641.

[xiv] Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, Jensen MD, Pories W, Fahrbach K, Schoelles K. Bariatric Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA 2004; 292: 1724-1737.

[xv] Fried M, Miller K, Kormanova K. Literature review of comparative studies of complications with Swedish band and Lap-Band. Obes Surg 2004; 14(2): 256-60.

[xvi] Crookes PF. Surgical treatment of morbid obesity. Annu Rev Med 2006; 57:243-64.

[xvii] Scopinaro

N, Gianetta E, Adami GF, Friedman D, Traverso E, Marinari GM, Cuneo S,

Vitale B, Ballari F, Colombini M, Baschieri G, Bachi V. Biliopancreatic diversion for obesity at eighteen years. Surgery 1996; 119(3): 261-8.

[xviii] Lee

CM, Cirangle PT, Jossart GH. Vertical gastrectomy for morbid obesity in

216 patients: report of two-year results. Surg Endosc 2007.

[xix] American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery: Position Statement on Sleeve Gastrectomy as a Bariatric Procedure. http://www.asbs.org/Newsite07/resources/sleeve_statement.pdf. Accessed 6 February 2008.

[xx] Cottam D, Qureshi FG, Mattar SG, et al. Laparoscopic

sleeve gastrectomy as an initial weight-loss procedure for high-risk

patients with morbid obesity. Surg Endosc 2006; 20(6):859-63.

[xxi] Bohdjalian A et al. One-year experience with Tantalus. Obes Surg 2006; 16(5): 627-34.