Author: Anne Peters, MD, FACP, CDE Director, USC Clinical Diabetes Programs Los Angeles, CA

2010-10-11What is type 1 diabetes?

2010-10-11What is type 1 diabetes?

Type 1 diabetes is a disease that often starts in childhood and was

previously known as “juvenile onset” diabetes, but we now know that it

can start at any age. People with type 1 diabetes have stopped making

insulin from the beta-cells in their pancreas, so they depend on insulin

injections for life. Type 1 is much less common than type 2 diabetes

(1-2 million individuals have type 1 diabetes in the United States

compared to 19 million who have type 2), but it often has a much more

sudden start, with patients (particularly children) becoming very ill

and requiring hospitalization for treatment. Although not curable, type

1 diabetes is very treatable with the appropriate care.

In some ways, type 1 diabetes is a simple disease. It is an autoimmune process which means it is a process in which the body’s infection-fighting response incorrectly destroys its own cells; in this case the infection-fighting response destroys the insulin-producing cells in the pancreas (the beta-cells). Therefore patients with type 1 diabetes stop making their own insulin and are completely dependent on insulin for life. (Although as with all diseases there are shades of gray; often early in type 1 diabetes people can make a little bit of their own insulin, with this gradually going away over time). Type 1 diabetes is different from patients with type 2 diabetes, who have both insulin resistance and insulin deficiency and have more treatment options than insulin alone.

An unusual increase in thirst is often a sign of developing type 1 diabetes.

The classic example of someone who gets type 1 diabetes is a skinny kid

who over the course of a month becomes very ill, with weight loss and

an increasing, insatiable thirst. Usually there is no family history of

diabetes, so the parents don’t know to watch out for it. By the time

the child is brought to the doctor or the emergency room they are very

sick, usually with a condition known as diabetic ketoacidosis or DKA.

DKA happens when there is so little insulin in the body that the body

breaks down fat for fuel. Too much fat breakdown leads to the excessive

build up of ketones (a by-product of your body burning stored fat) in

the blood and this can cause serious problems if not treated.

The diagnosis of diabetes is often a complete and devastating shock.

Suddenly everything must be learned about taking care of diabetes. All

of the information about what to eat, and what high and low blood sugar

levels mean, and how to test blood sugars and give insulin injections

must be assimilated over the course of a week. Usually this week is

spent in the hospital, teaching the child and their family about the

basics of diabetes and how to deal with it once they are sent home.

This is a lot to deal with all at once, and the child and everyone in

their family needs lots of help and support as they learn to cope with

the diagnosis.

There is also another, more slowly

starting form of type 1 diabetes that happens in adults. This is called

latent autoimmune diabetes of the adult (LADA). It is often confused

with type 2 diabetes, because both can happen in older patients (my

oldest patient with newly diagnosed LADA or type 1 diabetes is 93 years

of age). It is a more gradual process than is seen in childhood onset

type 1 diabetes and initially is often treated like type 2 diabetes,

with a slow evolution to insulin dependence.

What is the role of the pancreas?

As described above, type 1 diabetes means that the insulin secreting

cells in the pancreas, the beta-cells, are destroyed. This usually does

not mean that the whole pancreas stops working (unless you have had it

surgically removed), just the little cells that make insulin.

The pancreas itself is a squishy organ that is located in the middle of

the abdomen. Most of what the pancreas does is to secrete enzymes into

the intestines when food is eaten. These enzymes help digest food. If

the pancreas is removed or destroyed by a disease like cystic fibrosis,

it is necessary to take enzyme pills every time food is eaten to help

with digestion.

|

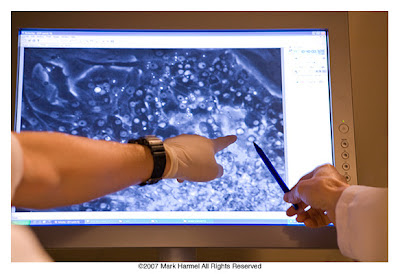

| Confocal microscope images of pancreatic islet cells at the Larry L. Hillblom Islet Research Center located at UCLA. |

Little

islands of cells are scattered in the tissue that makes the digestive

enzymes in the pancreas. These cell clusters are called islet cells.

They make substances called hormones that are released into the blood

stream. The main cells in the islets are beta-cells which make insulin

and amylin, plus alpha cells which make glucagon (a hormone that

increases blood sugar levels, instead of lowering it like insulin).

There are also delta-cells, which make other hormones that we don’t know

much about.

In type 1 diabetes the body makes a protein –

called an antibody – that is normally made to destroy unwanted bacteria

in our bodies. In this case the body is fooled into making antibodies

against a part of itself, the beta-cells. When these antibodies attach

to the beta-cells they cause the cells to die. Interestingly these

antibodies are so specific that they only attack the beta cell, which is

why early in the disease process glucagon is still released from the

alpha cells. For some reason the alpha cells lose their ability to

release glucagon after about five years, which makes people more

susceptible to low blood sugar reactions.

People don’t lose all

of the function of their beta-cells all at once, even if it sometimes

seems that way. What happens is that the cells are slowly killed off

over time. At the point where about half of the beta-cells are lost

blood sugar levels start to increase. Sometimes, when someone gets a

virus or another illness, they become resistant to the action of

insulin. This happens in everyone, but if the beta-cells are partly

destroyed your blood sugar levels can climb and you can quickly become

quite ill.

Sometimes people have surgery to remove most or all

of their pancreas. This not only gets rid of the beta-cells, but also

the alpha cells. People wake up from removal of their pancreas with

sudden, very brittle diabetes. These people functionally have a form of

type 1 diabetes, although some people categorize it differently because

it isn’t due to an autoimmune process.

What is the role of measuring antibodies in the blood?

The antibodies that circulate in the blood and destroy the beta-cells

can be measured. Measurement of antibodies can be helpful to determine

the type of diabetes and confirm the diagnosis. In children with new

onset type 1 diabetes three antibodies are measured, and are often

positive at the time of diagnosis: anti-islet cell antibodies,

anti-insulin antibodies and anti-GAD antibodies. In adults with new

onset type 1 diabetes, anti-GAD antibodies are often positive (and they

remain positive over time). Measurement of anti-GAD antibodies can be

helpful in distinguishing type 1 from type 2 diabetes, especially when

an adult without typical risk factors develops diabetes (see below).

What is latent autoimmune diabetes of the adult (LADA)?

Older individuals who develop diabetes, particularly those who are not

overweight and who do not have a family history of type 2 diabetes

should be tested to see if they really have slowly evolving type 1

diabetes. The blood test for this is called an anti-GAD antibody. If

the level is elevated it might mean that the beta-cells are being slowly

destroyed and treatment with insulin may be required. Some call LADA

type 1.5 diabetes, since it can start as a confusing intermediate

between type 1 and type 2 diabetes. However, since it is a slowly

destructive process of the beta-cells, LADA is the more specific term.

Zippora Karz, New York City Ballet soloist who was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes at 21.

Which adults should be tested for type 1 diabetes (LADA)?

Adults (from age 18 up) who develop diabetes and who are lean to normal

weight, not from a high risk ethnic groups for type 2 diabetes (Latino,

African American, Asian American, American Indian, Pacific Islander),

and without a family history of type 2 diabetes are more likely to have

type 1 diabetes. Also, not responding well to oral medication used for

the treatment of type 2 diabetes may mean the diagnosis of type 1

diabetes (LADA) is more likely.

What happens after the diagnosis of diabetes?

First find a healthcare team. The American Diabetes Association lists certified diabetes education programs

that can provide education and resources. Additionally, if possible

find an endocrinologist. Type 1 diabetes is fairly uncommon and most

doctors in general practice only have a few individuals with the

disease. Treating someone with type 1 diabetes means interpreting data,

reviewing blood sugar levels, providing insulin doses, and counting

carbohydrates. It means using the newest technology available for

monitoring and treating the disease. Often the physician isn’t the best

person for doing a lot of the day-to-day management — working with a

diabetes educator is often the best method – but normally general

practice doctors don’t have a diabetes educator and a dietitian working

with them. An endocrinologist usually will have both.

lists certified diabetes education programs

that can provide education and resources. Additionally, if possible

find an endocrinologist. Type 1 diabetes is fairly uncommon and most

doctors in general practice only have a few individuals with the

disease. Treating someone with type 1 diabetes means interpreting data,

reviewing blood sugar levels, providing insulin doses, and counting

carbohydrates. It means using the newest technology available for

monitoring and treating the disease. Often the physician isn’t the best

person for doing a lot of the day-to-day management — working with a

diabetes educator is often the best method – but normally general

practice doctors don’t have a diabetes educator and a dietitian working

with them. An endocrinologist usually will have both.

How is insulin used in type 1 diabetes?

Type 1 diabetes is treated with insulin injections designed to mimic

the action that the beta-cells in the pancreas once performed. Someday

there may be other ways to treat and even cure type 1 diabetes, but for

now the only way to get insulin into the body is with injections (or

through an insulin pump). No other way works well enough. Oral insulin

doesn’t work because insulin in the stomach is destroyed by acid. The

recent option of inhaled insulin has been taken off the market.

Fortunately current technology has made the needles on insulin syringes

and pens very small so that injections hardly hurt, which makes giving

shots easier than it used to be.

General Philosophy About Insulin

In someone who doesn’t have diabetes, the pancreas is able to make just

the right amount of insulin to mesh with the food that is eaten and the

body’s own production of sugar. The pancreas makes a little bit of

insulin all of the time, 24 hours a day. This is called the basal

insulin level. The basal insulin is the amount of insulin needed to

compensate for the sugar made by the liver. In theory, if no food is

eaten the basal insulin level keeps the blood sugar levels

constant—neither too high or to low. When someone without diabetes

doesn’t eat, the blood sugar level stays stable because of the interplay

of normal hormones and the production of sugar from the liver.

Every time a person eats carbohydrate (meaning sugar, since all

starches and simple sugars are sugar in the blood) the blood sugar level

goes up. This tells the pancreas to release more insulin. The more

carbohydrate (sugar) that is eaten, the more insulin the body makes.

This is called the meal-time insulin or bolus insulin. Thus, in someone

without diabetes, the body has a low, basal level of insulin and

releases premeal bursts or boluses of insulin. This keeps the blood

sugar level normal all day long.

This graph demonstrates how a healthy pancreas releases a balanced amount of insulin to cover the basal and bolus requirements.

In someone with type 1 diabetes, the pancreas makes no insulin, and insulin shots are given to mimic what the normal pancreas would do. The goal is to match the pattern of giving a basal insulin and then doses of insulin each time food is eaten. The nondiabetic pancreas knows what the blood sugar level is every second. To mimic this, the diabetic patient must test the blood sugar level before every meal and at bedtime (and often before snacks and exercise).

The goal in treating type 1 diabetes is to adjust the insulin to a

person’s lifestyle, rather than the other way around. Some diabetes

patients have fixed doses of insulin or use fixed mixtures of fast and

slow insulin such as 70/30 or 75/25, but these insulins provide very

little flexibility. With the proper care diabetes doesn’t need to be a

lifestyle limiting disease; people with type 1 diabetes have won Olympic

gold medals and are professional race car drivers.

|

| Indy Lights driver Charlie Kimball manages the twists and turns of the race course as well as his blood sugar. |

What are the types of insulin?

To understand the use of insulin it is important to understand the

types of insulin that are available. In the old days, most insulin came

from animal sources like pork or beef. Now, nearly all insulin is

scientifically formulated to be identical to human insulin.

The most basic form of human insulin is regular insulin. This insulin

is clear in color and is just like the insulin that comes from the

pancreas. The problem with regular insulin is that it forms clumps

under the skin after injection, and these clumps slow down how quickly

it gets absorbed. To get around this absorption problem, drug companies

changed the structure of the insulin a little bit, so it is absorbed

more reliably and more quickly or slowly. These changed insulin

molecules are called insulin analogues and have revolutionized our

ability to treat people with type 1 diabetes because they can more

closely approximate normal insulin secretion.

Lispo Humalog, aspart Novolog and glulisine Apidra

are the three rapid acting insulin analogues. After injection, they

start to work quickly, which is the way a normal pancreas would

function. Glargine Lantus and detemir Levemir

are long acting insulin analogues, which stay in the body as a steady,

basal insulin. People with type 1 diabetes typically use a combination

of both, which helps them have less weight gain, fewer low blood sugar

reactions, and somewhat better glucose control than those on the older

insulins. People get their proper insulin doses either through multiple

injections throughout the day or from an insulin pump.

Insulin

is categorized by how fast it works it the body, how soon it peaks and

then how long it lasts. Notice how rapid acting insulins have a rapid

rise and fall while longer acting insulin builds more slowly to a stable

baseline before declining.

What is the “Honeymoon” Phase?

Insulin requirements may end up being less during the first few months

of having diabetes, something known as the “honeymoon phase,” in which

the beta-cells seem to recover a little bit of the ability to make

insulin and decrease how much insulin must be given by injection.

Keeping diabetes under good control from the start can prolong the

body’s ability to make its own insulin for several years, and although

insulin shots are still required, it is often easier control the blood

sugars when the body can participate.

How Is An Intensive Insulin Regimen Created?

To create a regimen that is similar to the body’s natural patterns,

patients must test their blood sugar levels before each meal and give

rapid acting insulin in order to deal with the carbohydrate eaten at

that meal. In addition, the insulin dose must be adjusted if before

eating the blood sugar is too high or too low. The once or twice a day

dose of long acting insulin creates a base to help keep the blood sugar

level steady overnight, which leads to a more normal blood sugar.

The

long acting insulin is given once (usually glargine [Lantus]) or twice

(usually detemir [Levemir]) daily to provide a base, or basal insulin

level. Rapid acting (RA) insulin is given before meals and snacks. A

similar profile can be provided using an insulin pump (discussed later

in this Knol) where rapid acting insulin is given as the basal and

premeal bolus insulin.

What are the blood sugar targets?

Blood

sugar is the measurement of glucose levels in the blood. Depending on

where in the world you live, the units for blood sugar levels are

different. In the United States it is reported as mg/dL or milligrams

per deciliter. In most of the rest of the world the standard is mmol/L

or millimoles/liter. To convert from one to the other divide the value

in mg/dL by 18. So if the blood sugar level is 90 mg/dl in the United

States it is 5.0 mmol/l in Great Britain (90 divided by 18). Blood

sugar meters are coded based on the country of origin, although an

occasional patient may change from one set of units to another by

mistake, and become confused. The meter below reads 159 mg/dL (or 8.8

mmol/L). Because the author is from the United States, all blood sugar

levels in this article will be presented first as mg/dl, followed by

mmol/L). Another test, called the hemoglobin A1c or HbA1c is measured

once every three months to determine the average blood sugar levels over

the past three months. The units of HbA1c are universal.

|

| Testing with blood glucose meter throughout the day can help with the balancing act of keeping your blood sugar in the desired range . |

The

desired range of blood sugar levels is a blood sugar in the mornings

and before meals is between 80 – 130 mg/dL (4.4 - 7.22 mmol/L). This is

slightly higher than the blood sugar level in a nondiabetic person, but

it is set a bit higher to help avoid low blood sugar reactions. Low

blood sugar reactions occur when the blood sugar falls below 70 mg/dl

(3.9 mmol/L). The first symptoms of a low blood sugar reaction are

often feeling shaky, hungry, sweaty, and jittery. If some (15 – 30 gm)

rapid acting carbohydrate (4 - 8 ounces [12 - 24 ml]) of juice or

regular soda, or 3 – 6 glucose tablets) is not consumed, the blood sugar

level can fall too low which can cause the person with diabetes to

black out (lose consciousness). Therefore all people with type 1

diabetes should test their blood sugar levels throughout the day to be

sure they are not falling too low. They should also carry a form of

rapid acting carbohydrate with them at all times in case a low blood

sugar reaction occurs (this is discussed in more detail below).

Two hours after eating the blood sugar level should be less than 180

mg/dL (10 mmol/L) and if possible, slightly lower is better - someone

without diabetes has an after eating blood sugar level of less than 140

mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L). Finally, the HbA1c level (the 3 month blood sugar

average) should be less than 7%. The normal range for the HbA1c is 4 –

6% so ideally the HbA1c should be in the normal range. However, the

problem with trying to keep blood sugar levels normal is that the risk

of low blood sugar reactions increases. So treating type 1 diabetes is

always a balancing act of trying to keep blood sugar levels from being

too high or too low.

If blood sugar levels are too high

over time, the complications of diabetes can develop. These include

diabetic eye disease (retinopathy), kidney disease (nephropathy) and

nerve damage (neuropathy). These complications are the same in people

with both type 1 and type 2 diabetes, and are discussed in more detail

in the chapter on type 2 diabetes.

As with type 2 diabetes, achieving and maintaining near normal blood

sugar levels can help prevent the development of these complications, or

delay their progression if complications already exist.

How are blood sugar levels tested?

Meters

are the devices used to test your blood sugar level and new ones are

coming out all the time. The newer meters are smaller, faster, take

smaller drops of blood, and do not require coding (which means entering

the lot number of the strips into the meter each time a new vial of

strips is used). Some of them have self-contained strips, others have

memories that store information about insulin doses and lifestyle, or

alarms that provide reminders to test blood sugar levels. Meters

themselves are not expensive, and can often be obtained for free. It is

the strips for testing blood sugar levels that are costly. This is

usually covered if you have insurance.

Having an

accurate meter is important. A blood glucose meter can be brought in

and compared to a blood sample in the doctor’s office. Meters also have

calibration solutions that test to be sure the meter is functioning

correctly. It is important to keep the meter clean and use strips that

are not expired and kept in the closed container they are provided in.

The strips are the most fragile part of the system, and exposure to air

or heat can change their accuracy.

To test the blood sugar level a test strip is inserted into the blood sugar testing meter. Then a lancing (pricking) device is used to poke the finger and obtain a small drop of blood. The drop of blood is brought to the strip (or the strip/meter is held up to the drop of blood) and the appropriate part of the strip is brought into contact with the blood. Some blood is automatically drawn up into the strip and the chemical reaction between the blood and the solution on the strip produces a signal that the meter reads as a blood sugar level. This level is displayed on the screen in 5 – 30 seconds. Each meter works slightly differently, and all come with complete instructions that should be reviewed.

Some individuals prefer forearm

(instead of fingertip) testing. Forearm testing is only accurate if

blood sugar levels are stable, that is not rising or falling.

Unfortunately, it is hard to tell if blood sugar levels are rising or

falling before choosing to poke the forearm or a fingertip. This can

lead to falsely high blood sugar readings and low blood sugar

reactions. So if in doubt, use your fingertips.

How Are Insulin Doses Determined?

As mentioned above, intensive insulin therapy requires a basal insulin

dose. This can either be given through an insulin pump (described

below) or by giving an injection of long-acting glargine insulin or

detemir insulin. The glargine insulin is usually given once a day, in

the morning or the evening. Some people need to take it twice a day,

but most of the time it is a once a day insulin. Detemir is often given

twice a day, but can also be given once a day in some people. The dose

of glargine or detemir will be determined by the physician, and will be

roughly equal to half of the total daily dose of insulin. Lean

patients with type 1 diabetes generally have a dose that is somewhere

between 10 and 20 units, although the dose can vary and needs to be

determined individually. For the insulin pump, a basal rate or basal

rates are determined by your healthcare team. This is generally between

0.6 to 1.5 units of insulin per hour and this is what the pump is

programmed to give you, day in and day out.

In addition to

the basal rate insulin, a faster acting insulin is needed before eating

and if the blood sugar level happens to be high. The premeal insulin

doses are always based on two components. The first part is a

calculation based on how much carbohydrate is going to be eaten since

the carbohydrate component of the meal is the part that increases the

blood sugar level (see nutrition section below). The calculation is

either based on grams of carbohydrate or following the exchange system

where 1 unit of rapid acting insulin = 15 grams of carbohydrate (see

below). Carbohydrate counting is one of the hardest parts of diabetes

management to do well, and yet if done correctly it makes a big

difference in control of the blood sugar levels. The best way to learn

this skill is to work with a dietitian who can teach you how to do it.

Additionally, having a book that lists a variety of foods and their

carbohydrate content is helpful. Finally, weighing and measuring food

for the first month can be useful because it trains your “carb” counting

brain. After a month of working at carbohydrate counting it becomes

second nature.Once you determine the amount of carbohydrate in the meal, you determine your dose of insulin. This ratio, called the carb ratio, is adjusted for each person, but often begins with one unit of rapid acting insulin (lispro, aspart, or glulisine given through the pump or by injection) for every 15 grams of carbohydrate (or 1 exchange). For example if two 15 gram pieces of bread are to be eaten, two units of insulin would be taken before the meal.

The second part of the equation

is a correction factor for the level of blood sugar level before

eating. So if the blood sugar level is too low less insulin is given

and if it is too high more insulin is given. A target level blood sugar

is chosen, say 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L). If one unit of insulin drops

the blood sugar level 50 mg/dL (2.8 mmol/L), then the correction factor

is 50 (2.8). So if the blood sugar level is 250 mg/dL (13.9 mmol/L), 3

extra units (150 mg/dL divided by 50 or 8.3 mmol/L divided by 2.8) are

given to correct it down to 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L). Now this doesn’t

always work perfectly, but as you can see adjusting your insulin like

this lets you account for changes in your diet and your blood sugar

levels.

Adjustments are also made for exercise. When

exercising insulin is used more efficiently in the body and less needed

(except in certain circumstances, discussed below). Therefore, the

insulin dose may be reduced for the meal before exercise, to avoid a low

blood sugar reaction. Sometimes less insulin is given after you

exercise, as well. The best way to determine the insulin needs for

exercise is to carefully track blood sugar levels before and after

exercise for a few days, and then work with your diabetes health care

team to figure out what your insulin doses should be.

There

are several books devoted to teaching insulin dose adjustment for

individuals on multiple injection regimens and insulin pumps. These

books include: Using Insulin, Pumping Insulin and Taking Control of Your Diabetes, Third Edition.

These books go through the theory and practical use of intensive

insulin regimens and include worksheets on insulin dosing. Although

these books can be helpful, everyone should have an individual teacher.

In addition, in larger cities look for diabetes support groups. A

general diabetes support group, where most of the patients will have

type 2 diabetes and be on pills may not be all that helpful. Try to

find a support group for people on insulin pumps, or younger individuals

with type 1 diabetes. It often helps to learn from others.

Diabetes camps

are another good way to meet and make friends with other children or

teens facing a similar challenge. These camps also provide educational

programs on diabetes management. Some camps are family oriented and

others give the parents a vacation from the daily demands of diabetes.

There are even “diabetes boot camps” for adults.

The best

way to communicate the responses of your body to insulin, food and

exercise, is to keep careful track of the information to review with

your diabetes team. Although it is something of an annoyance to keep

detailed log sheets, these are the key to evaluating whether or not your

insulin regimen is effective. After the initial set of adjustments to

figure out the correct ratios and basal insulin doses, it often suffices

to log data for a week or two before each appointment with your

diabetes team. Ask how much information is needed and how best to share

the data (email, mail, FAX or in-person).

Hypoglycemia

Hypoglycemia

is defined as a blood sugar level that is below 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L).

As described above, it is associated with the symptoms of being weak,

shaky, hungry, sweaty, or having a rapid heart beat that goes away with

eating some form of rapid acting carbohydrate. This sounds simple

enough, but sometimes the warning signs of hypoglycemia aren’t noticed

and a loss of consciousness can occur. The common warning signs of

hypoglycemia are the “adrenergic” symptoms — the weak, shaky, sweaty

feelings, which are signs that your body has released catecholamines

(norepinephrine and epinephrine) into the blood stream to help raise the

blood sugar level. If these adrenergic symptoms are lost, either

because diabetes has existed for a long time (which can cause what is

called an autonomic neuropathy, meaning the body loses the ability to

react to low blood sugars) or because low blood sugar levels happen too

often (causing an abnormal adaptation to low blood sugar levels),

patients only have the neuroglycopenic symptoms, which is when the blood

sugar level falls below a certain level and the brain stops working

correctly. This means that instead of having a warning sign a person

will become confused, start slurring words, and may have a seizure or

sink into a coma. This is all because the brain uses sugar as its sole

source of fuel. These serious low blood sugar events (called severe

hypoglycemic reactions) usually require the help of someone else to

recover from them, either by injecting glucagon or calling 911 in the US

or the equivalent emergency help phone number in your country.

It is important to avoid these severe reactions, especially when

driving a car. Fortunately, most people with type 1 diabetes only have

one or two severe episodes in their lifetime, although some have them

more frequently and need careful treatment to prevent them from

happening. This is different from the less serious, easily recognized

and treated mild hypoglycemic reactions which generally occur several

times per week in well-controlled individuals with type 1 diabetes.

|

| The new continuous glucose monitors help to fill in the picture in between standard meter readings. |

How is hypoglycemia treated?

Treating mild hypoglycemia is something of an art. Most people hate the feeling of having a low blood sugar reaction and want to use it as an excuse to eat the food they have learned to avoid, like candy, soda, and cake. But if a low blood sugar is treated with too much sugar, glucose levels will skyrocket up again and then a situation can develop in which blood sugars yo-yo up and down and up again.

To avoid

overtreating low blood sugar reactions follow the rule of 15. If the

blood sugar is below 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L) and above 50 mg/dL (2.8

mmol/L), eat 15 grams of fast acting carbohydrate (see suggestions

below), wait 15 minutes, and recheck the blood sugar. If it is above 70

mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L) the hypoglycemic reaction is being treated. If the

blood sugar is not increasing, eat 15 additional grams of carbohydrate

and continue following the steps, until the blood sugar level is above

70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L). If the starting blood sugar is below 50 mg/dL

(2.8 mmol/L), eat 30 grams of carbohydrate and follow the steps above,

eating 30 grams of carbohydrate instead of 15 grams. Examples of 15

grams of simple carbohydrate are: three glucose tablets, 1/2 cup (four

ounces or 12 ml of juice), 1/2 can sugary soda, six Lifesavers, one cup

(eight ounces or 24 ml) milk, two tablespoonfuls (3 ml) of table sugar,

one tube of glucose gel. It is very important that all people with type

1 diabetes carry simple carbohydrate with them at all times!

After treating a low blood sugar reaction, eat a snack or a meal

containing fat, protein and carbohydrate within half an hour. This to

ensure that the blood sugar level stays in the normal range; otherwise

the effect of the simple carbohydrate, which raises the blood sugar

quickly, can wear off and the blood sugar level may drop again.

If a person with type 1 diabetes has a severe reaction and can’t eat or

drink a simple carbohydrate, then a family member or friend can give an

injection of glucagon. Glucagon is sort of an anti-insulin and raises

the blood sugar level fairly rapidly. However, people often forget to

keep glucagon on hand (it must be prescribed by a physician and expires

every six to 12 months). Also, the friend/relative of the person with

diabetes needs to be able to administer the injection. Instructions are

provided on the glucagon kit, but it helps to have practiced mixing up

the glucagon once before it has to be given in an emergency.

If glucagon isn’t available, call 911 in the US or the equivalent

emergency phone number. The paramedics have glucagon, as well as sugar

to give by vein, so they can easily help raise the blood sugar level.

No one should try to force a person with type 1 diabetes to drink juice

or eat sugar, especially if the person is unconscious. This could

result in juice being inhaled into the lungs, and that can cause serious

problems. Overall, although frightening and upsetting, these severe

reactions are treatable. It is important to contact your diabetes team

if one happens so they can help adjust your insulin (less insulin is

often needed the next day) and work on preventing another episode.

Because a reaction could occur when you are alone, it is very important

that you wear a medical alert bracelet. There are many companies who

make medical alert products. Some of these are: MedicAlert, American Medical-ID, Medic-ID, and ID-Tags.com. Some websites make nontraditional-looking medical alerts that are particularly good for children. Some examples are: MediCharms and Lauren'sHope. At the Children With Diabetes website a fairly complete listing of all of the medical alert providers is available.

What is carbohydrate counting and how is it done?

Counting carbohydrates is the key to success when living with type 1

diabetes. All people with type 1 diabetes do this, whether it is

conscious or unconscious. Because giving insulin shots mimics the role

of a pancreas, and a pancreas gives insulin based on how much

carbohydrate is eaten, there is no way to ignore the carbohydrate

content of the meal. Some people, with fixed regimens of insulin

(meaning the dose doesn’t vary much on a day to day basis) eat the same

amount of carbohydrate for each meal. Obviously this requires some

planning to have the right amount of carbohydrate in each meal. Others,

on the more flexible regimens, such as multiple daily injections and

insulin pumps, need to determine how many carbohydrates they want to

eat, and then adjust the insulin dose accordingly.

To

learn how to count carbohydrates accurately, make a study of it. It

takes several months of practicing to get good at it. The best way to

start learning about carbohydrate counting is to meet with a registered

dietitian who is an expert in diabetes. Additionally, there are books

and websites that can help. A few of these are: Complete Guide to Carb Counting, 2nd Edition, Barbara Kraus' Calories and Carbohydrates, and The CalorieKing.

Eating isn’t just about understanding carbohydrates (although carbs

have the most immediate effect on blood sugar levels). An overall

well-balanced diet is important, as well. Just as for all people, eat

healthy, unprocessed foods that are in high in fiber, vitamins, and high

quality nutrients. Limit the amount of saturated fat, trans fat and

cholesterol in your diet. Eat high quality lean protein in moderate

amounts. Each individual has their own best diet, and the dietitian can

help develop the overall meal plan.

What is a carbohydrate?

A

carbohydrate means the portion of the diet that breaks down readily to

sugar in the blood stream. Simple, refined sugars like table sugar are

absorbed quickly into the blood stream and raise glucose levels. More

complex sugars have to be broken down before they are absorbed, and are

often called starches, like pasta and rice and bread and potatoes. This

simply translates to all foods that are white, since with the exception

of egg whites and some types of fat, most white foods are sugars and

starches, and will raise blood sugar levels if eaten. Fruits,

vegetables and milk are also sources of carbohydrate. The goal of

creating a diet for each person with type 1 diabetes, is to incorporate

the foods you like to eat, in appropriate quantities, and to give the

necessary amount of insulin to cover the blood sugar rise following that

meal.

What is needed to learn carbohydrate counting?

In addition to a dietitian, three tools are: 1) a good guide listing

the carbohydrate content of foods, 2) a food measuring scale, and 3) a

set of measuring cups and spoons. Assemble the tools and start making

simple meals, measuring the grams of carbohydrate and giving insulin as

directed by your health care team. Doing this will build knowledge, and

eventually estimating the carbohydrate content of a meal will become

second nature.

Reading food labels

For prepared food the amount of carbohydrate in each serving is on the

label on the food container. In addition to noting the total number of

carbohydrate grams in a food, it is very important to note what the

designated serving size is. It is surprising how small a serving size

can be, and if more than one portion of food is to be eaten the

carbohydrate content needs to be proportionally increased.

A standard US food label found on many packaged foods.

What is the glycemic index?

The

glycemic index is a way of comparing one type of carbohydrate to

another carbohydrate. Although all carbohydrate raises blood sugar

levels, some types of carbohydrate raise your blood sugar levels more

than others. To study this researchers gave people with type 1 diabetes

a piece of white bread and measured how high it made the blood sugar

level go up after it was eaten. Based on that, the blood sugar response

to bread is set at 100. Other carbohydrates are compared to the

response to the bread. If another carbohydrate doesn’t make the blood

sugar go up as high as the bread it, it is said to have a lower glycemic

index. Carbohydrates that cause very little increase in blood sugar,

such as lentils, which have a glycemic index of 29, are considered low

glycemic index foods. When eating these foods less insulin may be

required for the same total amount of carbohydrate. Your dietitian can

teach you about adjusting for lower glycemic index foods. Some

recommend subtracting one unit of insulin for each five grams of fiber

eaten.

What are the effects of exercise?

People with type 1 diabetes have the same motivation to exercise as do

people without diabetes. Exercise helps maintain lean body mass and

fight the effects of aging. It helps lower rates of heart disease,

cancer, obesity, and osteoporosis. It also provides a sense of

well-being and helps with appearance. Exercise increases strength and

flexibility. It improves the fat in the blood stream, lowering

triglycerides, and increasing the HDL (good) cholesterol in the blood.

It helps fight stress and even improves sleep. Most people should

exercise five days a week for at least 30 minutes at a time and, ideally

up to one hour for each session.

Before starting an exercise program, check with your diabetes healthcare provider. If you are over 40 years of age you may need to have your heart checked before starting to exercise. If you have had diabetic eye damage your ophthalmologist should guide you as to what types of exercise are appropriate. People with nerve damage to their feet, especially if they have had foot ulcers and/or amputations should contact their podiatrist or other foot care provider to get advice on what shoes to wear and what kind of exercise is best. Finally, adjustments in insulin and carbohydrate intake will need to be made to avoid low blood sugar reactions since exercise improves sensitivity to injected insulin. A good resource is “The Diabetic Athlete” by Sheri Colberg and the Diabetes Exercise and Sport Association.

The best time to exercise is 90 minutes after eating. This is when the

rapid acting insulin is leaving the body and there is a good level of

sugar in the blood. If exercise will be moderate to strenuous the

premeal dose of insulin for the meal eaten before exercise may need to

be reduced. In addition, exercise during the day can lead to an

increase in insulin sensitivity overnight and some people need to

decrease their dose of basal or long acting insulin on the days they

exercise, or eat a bedtime snack to prevent low blood sugar levels while

they are sleeping. To learn how to make adjustments for exercise,

testing the blood sugar level before and after (and sometimes during)

exercise helps determine insulin doses and carbohydrate requirements.

The response to exercise may also change over time; usually exercise

lowers blood sugar levels, but when just starting out or performing very

intensive exercise, blood sugar levels can go up when stress hormones

(epinephrine and norepinephrine) are released.

Tools for Injecting Insulin

Although diabetes is not yet curable, the tools for managing diabetes

are becoming more and more refined. Simple advances can make a big

difference. For instance, insulin syringes come in a variety of

sizes—some hold only 30 units and have half-unit increments to make

measuring small doses easier. Needles come in different sizes and

lengths—mini, short and regular. A 31 gauge needle is the smallest (the

bigger the number the smaller the needle) and may hurt the least. The

physician writing the prescription for the needles (whether syringes

with needles or pen needles [see below]) must specify the length, gauge

and type of needle desired.

Insulin Pens

Insulin pens are wonderful devices that literally look like slightly thicker pens, which contain insulin and are dosed by turning a dial. The benefit of pens is that they avoid the fuss and bother of drawing up insulin from a vial with a syringe—the prefilled pens are ready to go. Some pens are completely disposable and others have replaceable cartridges. Either way, once a pen needle is screwed on the top of the insulin pen cartridge it is ready to use. With all pens the needle must be first flushed with insulin each time it is used to achieve an accurate dose. To flush the pen needle, dial up four to five units and push the plunger down and watch to see that insulin is flowing out the end of the needle. The pen is now ready to use. Pens are used very commonly in Europe and fairly rarely in the United States, largely due to differences in payment by insurance plans. With time, however, pen use is increasingly covered in the United States are more people are using them.

The steps for a proper injection are simple. Dial up the desired dose, insert the needle into the skin, push the plunger down and then wait for five seconds after the insulin is injected before removing it from the skin. These pens are easy to carry in a purse or backpack and are helpful when giving insulin injections before each meal. The down side to pens is that insulins can’t be self mixed (meaning mixed together by the patient) (although prefilled pens with insulin mixtures exist). Pens also have a limit to how much insulin can be given in one dose, often around 60 units. Finally, pens are often not covered by insurance companies because they are considered a convenience item, although being more convenient can hopefully translate to better control.

Insulin Pumps

Insulin pump therapy is another way of giving insulin, and is effective

for many people with type 1 diabetes. However, many individuals can

achieve good blood sugar control giving injections of insulin before

meals and a once or twice a day injection of basal insulin. There is no

one way to give insulin, and some people may prefer injections for a

few years and then switch to a pump or vice versa. The goal is to

safely and consistently bring blood sugar levels to normal and keep the

HbA1c below 7% without severe hypoglycemia. No matter which approach is

chosen it requires work and frequent blood sugar testing to make sure

that appropriate insulin doses are given.

An insulin pump is a

mechanical device, about the size of a pager, which provides a constant

flow of rapid acting insulin through a catheter that is inserted under

the skin. This catheter is inserted every two to three days with an

inserter that helps guide its placement. The catheter is connected to

the pump, which contains the insulin. The official title for this

therapy is “continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion” or CSII therapy.

Several companies make insulin pumps: Animas, MiniMed, Deltec, Accu-Chek, OmniPod.

|

| Medtronic MiniMed Paradigm® REAL-Time System - Courtesy Medtronic, Inc. |

A pump does NOT measure your blood sugar levels – you still have to prick your finger for that – but continuous glucose monitoring devices are being developed and blood sugar levels can be displayed on the MiniMed Paradigm pump’s LCD screen. The pump is filled with rapid acting insulin (lispro, aspart, glulisine) and it gives a slow little trickle of insulin based on a basal rate that is calculated by your diabetes healthcare team. Before each meal or snack information is entered into the pump consisting of the blood sugar level and the amount of carbohydrate to be eaten. The pump then calculates how much insulin to given, based on the preprogrammed carbohydrate and correction ratios. It asks the user if the user agrees with the dose and, if yes, the new dose is delivered. The user can always override the pump’s recommendations and give a different dose.

In some ways the pump

is much more convenient than shots—the insulin is ready to give, right

in the pump. But there are several things that make this system

difficult. For one thing the pump has to be worn somewhere on your

body. Men tend to wear it on their belts; women will often hide it in

their bra. At night the pump is worn on boxer shorts or a pajama top

with a pocket. The tubing is also a part of the device and must be kept

free of kinks and clogging, although the Omnipod pump attaches directly

to the body and does not require tubing. Finally, the flow of insulin

from the pump into the body is easily disrupted. If this happens for

too long a condition diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) can develop.

Therefore, the blood sugar level must be tested at least four times a

day. If it becomes high for no reason then insulin should be given by

injection and the pump infusion site changed.

There are many benefits to using an insulin pump. Unlike long acting insulin shots, which provide a fairly constant amount of insulin, the pump allows very small changes in the basal rate to be made in order to cover changing insulin needs during the day and particularly overnight. It is also easily turned off—it can be suspended or the basal rate reduced during exercise or if blood sugar levels drop too low. The newer pumps make it easier to do the complex calculations of carbohydrate and correction doses, as well as a calculation to tell you how much insulin is still acting in the body from the last insulin dose. Insulin doses from a pump can also be given in tenths of units, which is more precise than when given with an injection.

Continuous Glucose Monitoring Devices

Although methods for measuring blood sugar levels without finger pricks

do not yet exist, continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) is a technique

that has become increasingly helpful in the management of type 1

diabetes. These devices consist of a sensor that is inserted under the

skin (the sensor is about the size of a small piece of stiff fishing

line or the bristle in a hairbrush), and a transmitter that attaches to

the sensor and sends an infrared signal to the receiver. The receiver is

a pager-like device that can be worn on a belt or kept in a purse and

provides continuous information on glucose levels. Unlike many insulin

pumps, no tubing is involved. These sensors monitor the interstitial

(meaning the clear fluid just under the skin, not blood, although they

are calibrated as though they are reading a blood sugar level) sugar

levels every one to five minutes. Each sensor lasts from three to seven

days. The devices can be set to alarm if the blood sugar level is too

high or too low, but perhaps more importantly they can alarm if the

blood sugar level is falling or rising too quickly so that high and low

blood sugar levels can be avoided. For instance, if the blood sugar

level before a meal is 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) and falling quickly a

much smaller dose of insulin should be given than if the blood sugar is

100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) and rising rapidly.

Adjusting to all

of this new information is one of the concerns about using continuous

monitors. It could be dangerous if insulin is given every few minutes

because the blood sugar level is high, instead of giving insulin once

and then waiting for two to three hours for a response. Giving too much

insulin too often is dangerous. On the other hand, the added benefit

of being alerted to rising and falling blood sugar levels is very

helpful, and with training continuous glucose monitoring can be used

safely. The two sensors that are available are through Minimed (both with their pump and well as without) and Dexcom.

What is Symlin?

Symlin

(generic name: pramlintide) is structurally similar to a hormone called

amylin that is released from the beta-cells in the pancreas along with

insulin. In people with type 1 diabetes not only is the body producing

no insulin, but amylin production is deficient. Although amylin itself

can’t be injected because it forms clumps, a similar compound,

pramlintide can be given. What pramlintide does is to slow the

absorption of food (which is too rapid in most people with type 1

diabetes), lowers the after eating levels of glucagon (a hormone that

increases blood sugar levels), and reduces appetite. Thus Symlin can

lower blood sugar levels and weight if given before meals in patients

with type 1 diabetes.

Symlin is available in both

vials and in pens. The main side effect with Symlin is nausea and

sometimes vomiting. These side effects are reduced if a low dose is

used initially and gradually increased. It is given along with the

premeal insulin, although the insulin dose given before needs to be cut

in half when the Symlin is started in order to avoid low blood sugar

reactions. (If the Symlin leads to a decrease in appetite it would be

dangerous to give the usual dose of insulin and then end up eating

less). The specific recommendations for starting Symlin should be given

by the health care provider. Successful use of Symlin leads to a

reduction in the HbA1c level, a lower premeal insulin dose requirement

and some weight loss. People who shouldn’t use Symlin include those

with a gastroparesis (a condition whereby stomach emptying is too slow)

and patients who have out of control blood sugar levels.

| Researcher working at the Larry L. Hillblom Islet Research Center located at UCLA. |

Will there be a cure for type 1 diabetes?

The

best way to cure type 1 diabetes would be to find a way to turn off the

immune system so that it stops destroying the beta-cells. Researchers

are working hard to find a way to do this. Early studies have shown

some improvement, but turning off the immune system is a tricky business

because if done too much it can cause immune deficiency (for example

HIV/AIDS).

Another approach is to give more beta-cells (in the

form of islet cells), in the hopes that they will replace the missing

beta-cells. These islet cell transplants have been done at selected

centers in the United States and Canada, but there are several problems

with this procedure. First, it requires many islet cells and often

donations from two or more pancreases. Organ donations are limited,

making islet cells in short supply. Second, the person getting the

islet cells will destroy them (because they have type 1 diabetes) so

immunosuppressive drugs need to be given. These drugs have many side

effects and for many the side effects are worse than giving insulin

injections. Finally, over time the transplants fail and insulin use is

required again. So this is not a permanent solution.

Researchers are working on ways to overcome some of the barriers found

with islet cell transplantation. Stem cells may provide a good source

for islet cells. Certain cells in the body, such as liver cells, may be

transformable into islet cells so person could be their own source of

new islet cells. Encapsulation techniques are being researched so that

islet cells could be covered in a capsule that prevents them from being

destroyed but still allows them to function. Finally, newer and safer

immunosuppressive drugs are being developed.

Many organizations, such as the American Diabetes Association and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation are working towards a cure for type 1 diabetes. TrialNet is an international group of researchers who conduct research studies to help prevent and treat early type 1 diabetes and DirectNet is a consortium of researchers studying approaches for treating children with type 1 diabetes. Children with Diabetes is a group that sponsors programs for children with type 1 diabetes and their website has links to many diabetes resources.

are working towards a cure for type 1 diabetes. TrialNet is an international group of researchers who conduct research studies to help prevent and treat early type 1 diabetes and DirectNet is a consortium of researchers studying approaches for treating children with type 1 diabetes. Children with Diabetes is a group that sponsors programs for children with type 1 diabetes and their website has links to many diabetes resources.

Conclusion

The

treatment of type 1 diabetes is both simple and extremely complex.

Insulin must be given from the outside to mimic what the body should be

doing from the inside. The hardest part of type 1 diabetes for many

patients is the unrelenting quality of it: each day, all day, a person

with diabetes must test their blood sugar levels and react

appropriately. Although this can become second nature, it is still an

extra step that has to be performed before every meal, snack, and

activity. Fortunately, new technologies, such as continuous glucose

monitoring and highly effective insulin analogues, are being developed

that make living with diabetes a little bit easier. The good news is

that even if there is not yet a cure, type 1 diabetes is a disease that

can be treated effectively. People with type 1 diabetes are able to

live long and healthy lives, without the development of diabetic

complications that plagued earlier generations of people who suffered

from the disease.

Appendix: The Role of Diet in Type 1 Diabetes

With Meg Werner Moreta, RD, CDE

Meg Werner Moreta counseling a patient at the USC Westside Center for Diabetes.

Types of Carbohydrates

There are five basic types of carbohydrates: starches, simple sugars,

fruits, vegetables, and dairy. Fiber and alcohol (if consumed) are also

important dietary factors. Counting carbohydrates in all these foods

is easiest when eating at home, where it is relatively simple to weigh

and measure food. In contrast, when eating at a restaurant it is hard

to know everything that is added to food that can increase blood sugar

levels. Therefore, in restaurants it is helpful to ask for foods made

simply, (e.g., grilled foods without breading or a sauce).

Starches

Starches are long chains of sugar molecules and are often the hardest

food type to measure accurately. Often one starch increases the blood

sugar level more than another in an individual patient. For example,

some find a baked potato the most difficult, while others find pasta or

rice raise the blood sugar level most dramatically.

Whatever the response to any given starch, it is important to be able to measure it. This starts by figuring out portion size for carbohydrates. A general approach is that a basic portion size is 1/2 cup (70 gm) of cooked starch (such as pasta or potatoes), with most 1/2 cup (100 gm) servings equal to 15 grams of carbohydrate. Rice is the exception because it is extremely dense, so 1/3 cup (64 gm) of rice equals 15 grams. Note: Conversion of cups to grams (volume to weight) is tricky and is dependent on the food group. The on-line calculator found at GourmetSleuth can be a useful guide.

Whatever the response to any given starch, it is important to be able to measure it. This starts by figuring out portion size for carbohydrates. A general approach is that a basic portion size is 1/2 cup (70 gm) of cooked starch (such as pasta or potatoes), with most 1/2 cup (100 gm) servings equal to 15 grams of carbohydrate. Rice is the exception because it is extremely dense, so 1/3 cup (64 gm) of rice equals 15 grams. Note: Conversion of cups to grams (volume to weight) is tricky and is dependent on the food group. The on-line calculator found at GourmetSleuth can be a useful guide.

Other

starch servings that equal 15 grams of carbohydrate are one slice of

bread or 1/2 cup (70 gm) of potatoes, beans, garbanzo beans, kidney

beans, lima beans, lentils, squashes, peas, croutons, and corn. Since

many of these starches are added to salads or meals, it helps to measure

out 15 grams worth at home, to get a feel for what it will look like

when mixed into food when dining out.

Fruits

Fruits are a good source of carbohydrate and are filled with lots of

wonderful nutrients, minerals, and vitamins. Although the sugar in

fruit can increase blood sugar levels, fresh fruit generally contains

enough fiber to blunt some of the expected increase. Cooking fruit or

mashing it to make fruit juice often increases the amount of

carbohydrate consumed, lowers the fiber content, and increases the speed

at which your blood sugar levels rise. Therefore eat fresh, uncooked

fruit as much as possible, with the exception of really dense fruit,

like bananas, that can often raise blood sugar levels too high. The

portion size for a banana is half a banana—a whole banana is two

portions, or 30 grams.

The difficulty in counting fruit

carbs is that fruit doesn’t come in prepackaged sizes. Although

sometimes fruit in the grocery store looks like it was made in a

standard mold, natural fruit often varies in size. It also varies in

ripeness, which can alter how sweet (how much simple sugar) is in the

piece of fruit. In spite of this, it would be ideal to eat 3 to 4

pieces of fruit per day.

In order to incorporate fruit

into your diet, follow these general rules: a very small apple, a small

peach, or a small pear is 15 grams of carbohydrate. Bigger ones may

need to count as 20 to 25 grams. A banana or a grapefruit is worth 30

grams. Fruit juice should be avoided, except to treat a low blood sugar

reaction. However, if fruit juice is to be consumed 4 ounces (12 ml)

is 15 grams of carbohydrate.

Fruits are a good source of carbohydrate and are filled with lots of wonderful nutrients, minerals, and vitamins.

Vegetables

Vegetables should comprise half of the calories eaten each day. In the

past non-starchy vegetables were not counted when calculating

carbohydrate grams, but if one eats enough of them, vegetables will

raise blood sugar levels because they are, in fact, carbohydrates. In

general, assume that three cups (600 gm) of non-starchy raw vegetables –

or one and one-half cups (300 gm) of cooked vegetables – equals 15

grams of carbohydrate.

Dairy Products

Dairy products often have carbohydrate, fat, and protein in them. The

label on dairy products helps determine how many grams of carbohydrate

are in a serving. For milk, eight ounces (24 ml) equals 12 to 15 grams

of carbohydrate. Typically, it is best to consume low fat dairy products

to cut back on saturated fat and cholesterol consumption.

Simple Sugars

Simple sugars (e.g., non-diet sodas, large amounts of catsup, and the

high fructose corn syrup used in many foods) increase blood sugar levels

quickly. As discussed above, 15 to 30 grams of simple carbohydrate

should be used to treat a low blood sugar reaction. Fifteen grams of

sugar can be provided by the following: two tablespoons of table sugar,

one tablespoon (1.5 ml) of honey, four ounces (12 ml) of juice, or eight

ounces (24 ml) of milk.

General Philosophy

The key is to read and study and learn the carbohydrate content of all

of the things that are eaten. One needs to be a detective and find the

hidden carbohydrate calories so the insulin can be adjusted

appropriately. The more knowledge you have, the better you’ll function

as an artificial pancreas; the better you function as a pancreas, the

more normal your blood sugar levels will be.

Another

good rule is to log your food, estimated carbohydrate content, and

insulin dose given in real day. Using your logs, you and your

healthcare team can work together to see if your blood sugar levels are

within range both before and two hours after eating. Then you can adjust

your carbohydrate ratios and correction factors if they are not

covering your carbohydrate intake adequately.

The Effects of Fiber

Fiber slows down the absorption of food. It is actually very good for

everyone, because it helps digestion function normally. More fiber

lowers the glycemic index of food and reduces how high the blood sugar

levels are after eating. Refining food means breaking down the fiber

and increasing the speed at which it is absorbed. Accounting for the

fiber in food will help further improve accuracy in carb counting. In

general if the food to be eaten contains five grams of fiber or more, it

should be subtracted from the carbohydrate total for that meal.

The Effects of Protein and Fat on Blood Sugar Levels

Protein can be converted into sugar, but this generally happens so

slowly and gradually that it doesn’t really make an obvious difference

in blood sugar levels if only three or four ounces (85 - 113 gm) are

eaten. However, if 10 ounces (283 gm) or more are eaten, extra insulin

might need to be added to account for the fact that protein can turn

into glucose in the body over time. This function of protein, the slow

increase in blood sugar levels over time, means that it can help keep

blood sugar levels in the normal range in between meals or overnight.

Fat slows gastric emptying and can prolong the effects of

food in the gastrointestinal track. Foods such as pizza, which is high

in fat and simple carbohydrate, can increase blood sugar levels

immediately after eating and then several hours later as the food is

slowly absorbed. Fat will never turn into sugar itself, but by slowing

the absorption of carbohydrate, it can also help keep blood sugar levels

higher over time.

Alcohol

Although

it seems like alcohol should be sugar in the blood, its unique form

doesn’t usually raise blood sugar levels. In fact, pure alcohol reduces

how much sugar the liver makes, and it can lower the blood sugar

level. So when drinking alcohol it is important to eat some food at the

same time, in order to avoid low blood sugar reactions. An alcoholic

drink, however, doesn’t always lower the blood sugar levels, because

drinks are sometimes combined with sweet mixers; these should be taken

into account. Beer also has more carbs than wine. In short, it is

important to learn the impact of various types of alcohol on your blood

sugar levels.

From a health-perspective, drinking a

small amount of alcohol is probably a good thing, as long as there is no

history of alcohol addiction. Too much alcohol is clearly bad – brain

and liver cells start dying – but a glass of wine with dinner may help

lower the risk of heart disease. This has been studied in people with

and without diabetes. So although people who don’t drink shouldn’t

start drinking, people who drink in moderation and who have type 1

diabetes can continue. Just keep in mind the potential for low blood

sugar reactions overnight, especially if extra alcohol is consumed. Be

sure to eat a balanced meal and test blood sugar levels to avoid running

into trouble.

Diabetes Organizations:

- American Diabetes Association: http://www.diabetes.org/

- International Diabetes Federation: http://www.idf.org/

- National Diabetes Education Program: http://ndep.nih.gov/

- American Association of Diabetes Educators: http://www.diabeteseducator.org/

- American Dietetic Association: http://www.eatright.org/

- Diabetes Exercise and Sports Association (DESA): http://www.diabetes-exercise.org/

- Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation: http://www.jdrf.org/

- Children with Diabetes: http://www.childrenwithdiabetes.com/

- Center for Disease Control: http://www.cdc.gov/

- American Heart Association: http://www.americanheart.org/

- Comprehensive Foot Health Site: http://www.foot.com/

Patient Education Events

- Taking Control of Your Diabetes: http://www.tcoyd.org

- ADA Diabetes Expo: http://www.diabetes.org

- Green Mountain at Fox Run: http://fitwoman.com

People With Diabetes Blogs:

- Diabetes Mine by Amy Tenderich: http://www.diabetesmine.com/

- David Mendosa: http://www.mendosa.com/

- Diabetes Sisters: http://www.diabetessisters.com

Patient Education Websites

- For Your Diabetes Life: http://www.dlife.com/

- America on the Move: http://www.americaonthemove.org/

- How I Do Diabetes.com (Sponsored by Novartis): http://www.howidodiabetes.com/

- YourDiabetesGoals.com (Sponsored by Amylin): http://www.yourdiabetesgoals.com/

- Do>Groove (Sponsored by BlueCross/Blue Shield - MN): http://www.do-groove.com/

- Healthy Updates - Diabetes: http://www.healthyupdates.com/diabetes/

Anne Peters, M. D.

- USC Westside Center for Diabetes: http://www.uscdiabetes.com

- Keck Diabetes Prevention Initiative: http://www.wmkeck.org/contentManagement/PR_95271a31-9585-4508-a17c-67d8d0235b41.htm

- Peters AL. “Conquering Diabetes.” Hudson Street Press/Penguin Publications, New York City, New York, 2005. http://www.conqueringdiabetes.com/

- Dr. Anne Peters in the PBS series Remaking American Medicine "The Stealth Epidemic": http://www.remakingamericanmedicine.org/episode3.html

- Interview of Dr. Anne Peters on Diana Rehm -WAMU Audio: http://wamu.org/programs/dr/05/08/12.php

- Interview of Dr. Anne Peters on Exercising with Diabetes -Diabetes Health: http://www.diabeteshealth.com/read/2006/03/01/4528.html

- Transcript of Dr. Peters on Larry King Live: http://transcripts.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/0505/20/lkl.01.html

- Today Show videos (after an opening ad): Segment 1 - Segment 2

- Close Concerns interview.

Additional Links

Official website for Indy Lights driver Charlie Kimball: http://www.charliekimball.com/

Official website of dancer Zippora Karz: http://www.zipporakarz.com/

Photographer Mark Harmel: http://www.harmelphoto.com/