NIH: People spend about a third of their lives asleep. When we get too

little shut-eye, it takes a toll on attention, learning and memory, not

to mention our physical health. Virtually all animals with complex

brains seem to have this same need for sleep. But exactly what is it

about sleep that’s so essential? Two NIH-funded studies in mice now offer a possible answer. The two

research teams used entirely different approaches to reach the same

conclusion: the brain’s neural connections grow stronger during waking

hours, but scale back during snooze time. This sleep-related phenomenon

apparently keeps neural circuits from overloading, ensuring that mice

(and, quite likely humans) awaken with brains that are refreshed and

ready to tackle new challenges.

The idea that sleep is required to keep

the brain wiring sharp goes back more than a decade [1]. While a fair

amount of evidence has emerged to support the hypothesis, its

originators Chiara Cirelli and Giulio Tononi of the University of

Wisconsin-Madison, set out in their new study to provide some of the

first direct visual proof that it’s indeed the case.

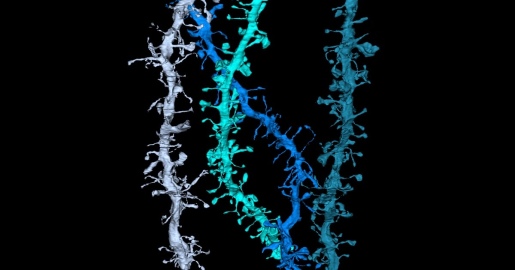

As published in the journal Science, the researchers used a

painstaking, cutting-edge imaging technique to capture high-resolution

pictures of two areas of the mouse’s cerebral cortex, a part of the

brain that coordinates incoming sensory and motor information [2]. The

technique, called serial scanning 3D electron microscopy, involves

repeated scanning of small slices of the brain to produce many thousands

of images, allowing the researchers to produce detailed 3D

reconstructions of individual neurons.

Their goal was to measure the size of the synapses, where the ends of

two neurons connect. Synapses are critical for one neuron to pass

signals on to the next, and the strength of those neural connections

corresponds to their size.

The researchers measured close to 7,000 synapses in all. Their images

show that synapses grew stronger and larger as these nocturnal mice

scurried about at night. Then, after 6 to 8 hours of sleep during the

day, those synapses shrank by about 18 percent as the brain reset for

another night of activity. Importantly, the effects of sleep held when

the researchers switched the mice’s schedule, keeping them up and

engaged with toys and other objects during the day.

In the second Science report, Richard Huganir and his

colleagues at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore,

measured changes in the levels of certain brain proteins with sleep to

offer biochemical evidence for this weakening of synapses [3]. Their

findings show that levels of protein receptors found on the receiving

ends of synapses dropped by 20 percent while their mice slept.

The researchers also show that the protein Homer1a—important in

regulating sleep and wakefulness—rises in synapses during a long snooze,

playing a critical role in the resetting process. When the protein was

lacking, brains didn’t reset properly during sleep. This suggests that

Homer1a responds to chemical cues in the brain that signal the need to

sleep.

These studies add to prior work that

suggests another function of sleep is to allow glial lymphatics in the

brain to clear out proteins and other toxins that have deposited during

the day. All of this goes to show that a good night’s sleep really can

bring clarity. So, the next time you’re struggling to make a decision

and someone tells you to “sleep on it”—that might be really good advice.

References:

[1] Sleep and synaptic homeostasis: a hypothesis. Tononi G, Cirelli C. Brain Res Bull. 2003 Dec 15;62(2):143-150.

[2] Ultrastructural evidence for synaptic scaling across the wake/sleep cycle. de Vivo L, Bellesi M, Marshall W, Bushong EA, Ellisman MH, Tononi G, Cirelli C. Science. 2017 Feb 3;355(6324):507-510.

[3] Homer1a drives homeostatic scaling-down of excitatory synapses during sleep. Diering GH, Nirujogi RS, Roth RH, Worley PF, Pandey A, Huganir RL. Science. 2017 Feb 3;355(6324):511-515.

Links:

Sleep and Memory (National Institute of Mental Health/NIH)

Why is Sleep Important? (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

Huganir Lab (Johns Hopkins, Baltimore)

Chiara Cirelli (University of Wisconsin, Madison)

Giulio Tononi (University of Wisconsin, Madison)

NIH Support: National Institute of Mental Health, National

Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Institute of

General Medical Sciences