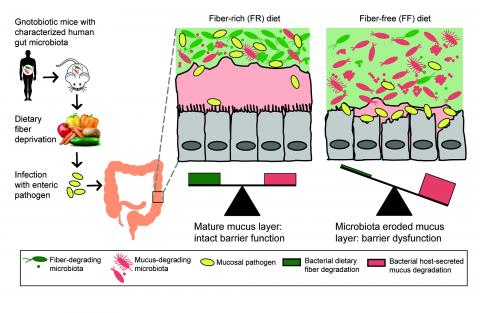

Starved, they begin to munch on the natural layer of mucus that lines the gut, eroding it to the point where dangerous invading bacteria can infect the colon wall.

In a new paper in Cell, (link is external) an international team of researchers show the impact of fiber deprivation on the guts of specially raised mice. The mice were born and raised with no gut microbes of their own, then received a transplant of 14 bacteria that normally grow in the human gut. Scientists know the full genetic signature of each one, making it possible to track their activity over time.

The findings have implications for understanding not only the role of fiber in a normal diet, but also the potential of using fiber to counter the effects of digestive tract disorders.

Using U-M’s special gnotobiotic, or germ-free, mouse facility (link is external), and advanced genetic techniques that allowed them to determine which bacteria were present and active under different conditions, they studied the impact of diets with different fiber content – and those with no fiber. They also infected some of the mice with a bacterial strain that does to mice what certain strains of Escherichia coli can do to humans – cause gut infections that lead to irritation, inflammation, diarrhea and more.

The result: the mucus layer stayed thick, and the infection didn’t take full hold, in mice that received a diet that was about 15 percent fiber from minimally processed grains and plants. But when the researchers substituted a diet with no fiber in it, even for a few days, some of the microbes in their guts began to munch on the mucus.

They also tried a diet that was rich in prebiotic fiber – purified forms of soluble fiber similar to what some processed foods and supplements currently contain. This diet resulted in a similar erosion of the mucus layer as observed in the lack of fiber.

The researchers also saw that the mix of bacteria changed depending on what the mice were being fed, even day by day. Some species of bacteria in the transplanted microbiome were more common – meaning they had reproduced more – in low-fiber conditions, others in high-fiber conditions.

And the four bacteria strains that flourished most in low-fiber and no-fiber conditions were the only ones that make enzymes that are capable of breaking down the long molecules called glycoproteins that make up the mucus layer.

In addition to looking at the of bacteria based on genetic information, the researchers could see which fiber-digesting enzymes the bacteria were making. They detected more than 1,600 different enzymes capable of degrading carbohydrates – similar to the complexity in the normal human gut.

Just like the mix of bacteria, the mix of enzymes changed depending on what the mice were being fed, with even occasional fiber deprivation leading to more production of mucus-degrading enzymes.

Images of the mucus layer, and the “goblet” cells of the colon wall that produce the mucus constantly, showed the layer was thinner the less fiber the mice received. While mucus is constantly being produced and degraded in a normal gut, the change in bacteria activity under the lowest-fiber conditions meant that the pace of eating was faster than the pace of production – almost like an overzealous harvesting of trees outpacing the planting of new ones.

When the researchers infected the mice with Citrobacter rodentium – the E. coli-like bacteria – they observed that these dangerous bacteria flourished more in the guts of mice fed a fiber-free diet. Many of those mice began to show severea signs of illness and lost weight.

When the scientists looked at samples of their gut tissue, they saw not only a much thinner or even patchy mucus later – they also saw inflammation across a wide area. Mice that had received a fiber-rich diet before being infected also had some inflammation but across a much smaller area.

“To make it simple, the “holes” created by our microbiota while eroding the mucus serve as wide open doors for pathogenic micro-organisms to invade,” explains Desai, who is Group Leader at LIH’s Department of Infection and Immunity.

Martens notes that in addition to the gnotobiotic facility, the research was possible because of the microbe DNA and RNA sequencing capability built up through the Medical School’s Host Microbiome Initiative, as well as the computing capability to plow through all the sequence data.

“Having all the resources here was the key to making this work, and the fact that it was all across the street from our lab allowed us to pin it all together,” he says. He also notes the role of U-M colleagues led by Gabriel Nunez and Nobuhiko Kamada in providing the C. rodentium pathogen model, and of French collaborators from the Aix-Marseille Université in studying the enzymes in the mouse gut.

Going forward, Martens and Desai intend to look at the impact of different prebiotic fiber mixes, and of diets with more intermitted natural fiber content over a longer period. They also want to look for biomarkers that could tell them about the status of the mucus layer in human guts – such as the abundance of mucus-digesting bacteria strains, and the effect of low fiber on chronic disease such as inflammatory bowel disease.

“While this work was in mice, the take-home message from this work for humans amplifies everything that doctors and nutritionists have been telling us for decades: Eat a lot of fiber from diverse natural sources,” says Martens. “Your diet directly influences your microbiota, and from there it may influence the status of your gut’s mucus layer and tendency toward disease. But it’s an open question of whether we can cure our cultural lack of fiber with something more purified and easy to ingest than a lot of broccoli.”

In addition to Martens, Desai, Nunez and Kamada and the French collaborators, the paper’s authors are U-M’s Anna Seekatz, Nicole Koropatkin, Nicholas Pudlo, Sho Kitamoto and Vincent Young, and colleagues from the Washington University School of Medicine and the Luxembourg Centre for Systems Biomedicine and the Luxembourg Institute of Health. The research was funded by the Luxembourg National Research Fund and Luxembourg Ministry of Higher Education and Research; the National Institutes of Health (GM099513) and the U-M Host Microbiome Initiative and Center for Gastrointestinal Research (DK034933).