Author: Dr Anthony J. Schaeffer University of Chicago 2008-07-28

Urinary tract infection in women is a common disorder that can be diagnosed and treated with simple and reliable techniques. The majority of these infections occur in a healthy woman with a normal urinary tract, and this article addresses the occurrence, misconceptions, and strategies for its prevention and treatment.

Urinary tract infection in women is a common disorder that can be diagnosed and treated with simple and reliable techniques. The majority of these infections occur in a healthy woman with a normal urinary tract, and this article addresses the occurrence, misconceptions, and strategies for its prevention and treatment.

Some patients, particularly the elderly, can have asymptomatic bacteriuria - a term used rather than UTI when no symptoms are present. UTI is presumptive when analysis of the urine (urinalysis) reveals bacteriuria, usually accompanied by white and red blood cells; a urine culture quantifying the number and type of bacteria present is required to document a UTI. Other conditions that mimic the symptoms of UTI include those which cause external irritation and dysuria such as vaginitis or urethritis, but these conditions have a gradual onset, milder symptoms, are associated with negative urine cultures, and are commonly accompanied by vaginal discharge [2]. Trauma to the vaginal opening (introitus) following intercourse or thinning of the vaginal lining cells due to aging and estrogen depletion can also contribute to symptoms that mimic UTI. Most UTIs in women result in significant morbidity and cost but are not associated with major health issues such as dissemination of bacteria to the blood stream or renal (kidney) damage. The focus of this Knol is on uncomplicated UTIs in women. Many of the principles described also apply to girls, but have their own special requirements for diagnosis and treatment not covered here.

How are Urinary Tract Infections Categorized?

All UTIs can be categorized by:- The status of the urinary tract

- The pattern of infection

- The site of infection

The status of the urinary tract - Uncomplicated UTIs typically occur in healthy women with structurally and functionally normal urinary tracts. Complicated UTIs are associated with a structurally or functionally abnormal urinary tract, a patient who is compromised by pregnancy for example, severe diabetes or spinal cord injury, or bacteria that are resistant to antimicrobial therapy.

The pattern of infection refers to the relationship of one infection to another. Isolated or sporadic infections are separated by long intervals. An unresolved UTI is one that does not respond to antimicrobial therapy, usually due to the resistance of the bacteria to the initially chosen therapy. Recurring infections refer to those occurring after resolution of a prior UTI.

The site of infection is based on assessment of the patient’s symptoms, physical findings, and/or imaging studies. Cystitis refers to an infection of the bladder characterized by irritative voiding symptoms (dysuria, frequency and urgency); if these symptoms are also associated with fever, chills, and flank pain, the patient is judged to have an upper tract (kidney) infection (pyelonephritis).

What Causes Urinary Tract Infections?

The bladder stores urine and is normally free of bacteria. UTIs are ascending events, meaning bacteria travel from outside the body, up through the urethra, and into the bladder. Uncomplicated cystitis is caused by uropathogenic bacteria: Escherichia coli (E. coli) in 80% of cases, Staphylococcus saprophyticus in 5-10% of cases, and occasionally Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella species, enterococci, or other microorganisms. For infection to occur the bacteria must have virulence factors which allow them to overcome the host defenses and/or the host has to have increased susceptibility (Figure 2).Bacterial Virulence Factors

Bacterial virulence factors are required for the bacteria to advance to the bladder. Bacterial fimbriae are hair-like, surface appendages that facilitate bacterial adherence to the cells lining the vagina, urethra, and bladder. Many other virulence factors come into play as the bacteria adapt to its changing environment in an effort to survive and subsequently grow within the urinary tract. More virulent bacteria are required to overcome a staunch host defense; conversely, bacteria with minimal virulence characteristics can successfully infect a compromised host (Figure 3).

Host Susceptibility

The vaginal introitus of most healthy women is colonized with a microflora including lactobacilli and contains few, if any, uropathogenic bacteria. However, in women who have UTIs, the bacteria transiently, or in some cases persistently, colonize this surface before ascending into the bladder. Research has also shown that the ability of bacteria to adhere to the vaginal mucosa is influenced by genetic alterations in the vaginal cell surface that make them more receptive to colonization by pathogenic bacteria [3, 4]. If bacteria are present on the vaginal introitus and urethra, sexual intercourse can facilitate inoculation of bacteria into the bladder [5, 6]. Factors such as spermicides [7, 8, 9], certain antimicrobial therapies, or lack of estrogen can alter this normal vaginal introital flora [10], promoting pathogenic colonization.

The primary bladder defense is complete emptying of the bladder. Conversely, a bladder that retains urine (retention) promotes development of UTI. Structural changes to the urinary tract causing it to dilate (as is associated with pregnancy), and metabolic abnormalities also facilitate UTI; for example glucosuria, the presence of sugar in the urine due to severe diabetes, does not appear to contribute to the frequency of the symptomatic infection but may contribute to the severity of the UTI.

Diagnosing Urinary Tract Infection

UTIs are diagnosed by assessment of the urine (Figure 4). A clean catch, mid-stream specimen provides the best opportunity for making an accurate diagnosis. The patient should cleanse the periurethral meatal tissues (the external and just internal surfaces around the vagina where urine is expelled), pass some urine, and then collect a mid-stream specimen into a sterile container. If a specimen is obtained with poor technique, resulting in contamination of the cells from the vaginal introitus, a false positive result will be obtained and the patient will be inappropriately diagnosed as having a UTI.Two types of urinalysis are performed for identification of bacteria and blood cells. The dip slide is a common, convenient, fast, and inexpensive office test that indirectly detects bacteriuria and pyuria (white blood cells in the urine). If the presence of either bacteriuria or pyuria is considered positive, the detection rate (sensitivity) and the accuracy (specificity) approach 95% [1]. Microscopy, which provides direct visualization of cells and bacteria, uses similar criteria in its analysis and has a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 90% [11]. A positive urinalysis provides presumptive evidence of a UTI. Definitively diagnosing a UTI requires a urine culture, which will quantify the number and species of bacteria present; 1000 or more bacteria per millimeter of urine is consistent with a positive urine culture [12]. Culture takes 24-48 hours and is costly.

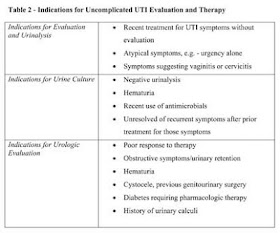

In a healthy woman judged to have an isolated uncomplicated UTI, it is not necessary to obtain a urine culture. A culture should be performed if the patient has atypical clinical features such as symptoms without bacteriuria or pyuria, or if there are other factors such as recent exposure to antimicrobial agents that could render the bacteria more resistant to therapy. Patients with symptoms and negative urinalysis and/or urine cultures should be evaluated for other conditions that mimic the symptoms of UTI, such as bladder cancer or interstitial cystitis (an inflammatory bladder condition).

What Can Reduce the Risk of a UTI?

Complete voiding and avoidance of spermicides may reduce the risk of developing a UTI. However, studies show that post-intercourse voiding does not reduce the likelihood of developing a UTI [5, 6, 13, 14].Treating Urinary Tract Infection with Medication

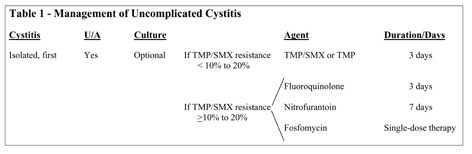

Symptomatic cystitis should be treated with antimicrobial therapy to eradicate the bacteria from the bladder and reduce symptoms (Table 1). Oral medications that are effective against the pathogen, inexpensive, and safe are most desirable. The recommended duration of therapy is 3 days with the exception of nitrofurantoin, which is recommended for 7 days. Single-dose therapy is generally less effective and results in more recurrences. Therapy for 7 days or longer is not more effective, is more costly, and causes more side effects such as vaginitis or skin rash.Bacteria causing uncomplicated cystitis in the United States are frequently resistant to penicillins, cephalosporins, sulfamethoxazole (approximately 30-50%), and nitrofurantoin (15-20%). Resistance to trimethoprim and trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole has increased to 20-25% and varies geographically; resistance to fluoroquinolones is usually below 5%, but rising as utilization increases. Bacterial resistance is more likely in patients who have been recently exposed to antimicrobials.

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole/ trimethoprim

- Currently considered the first choice for therapy

- Overall clinical and bacterial cure rates of 80 to 85% can be expected [1, 15]

- Added benefit of eliminating pathogenic bacteria from the vaginal flora and are generally cost effective and safe

- Trimethoprim alone is as effective as the trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole combination and may be associated with fewer side effects

- Disadvantages include relatively common side effects consisting primarily of skin rash and gastrointestinal complaints (nausea, diarrhea, vomiting)

Fluoroquinolones

- Highly effective and well-tolerated, but generally more expensive than trimethoprim or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole

- Reduce pathogenic bacteria in the vaginal flora

- Should be used primarily in patients who fail therapy with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim or nitrofurantoin, to treat infections in patients allergic to other drugs, and in infections caused by bacteria presumed or known to be resistant to other antimicrobial agents

- All quinolones are probably equivalent

- Adverse reactions are uncommon, and include headache, dizziness and restlessness, with gastrointestinal disturbances and skin reactions infrequent; rare occurrences of Achilles tendon disorders, including ruptures, have been reported, thus they should not be given to patients with Achilles tendonitis and discontinued at the first sign of tendon pain

- Antacids containing magnesium or aluminum interfere with absorption of fluoroquinolones

Nitrofurantoin

- Effective against E. coli and enterococci but not against most other uropathogens

- Secretion is limited to the urine

- Minimal effects on the bowel and vaginal flora, and bacterial resistance to this drug is exceedingly low

- Nitrofurantoin is given for 7 days

- Frequently causes gastrointestinal upset (loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting) and headache

Fosfomycin

- Taken as a single dose; expensive

- Less effective than trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or fluoroquinolones [16]

- Used when other agents can not be used

- Adverse reactions include gastrointestinal complaints (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea) and vaginitis

Beta-lactams

- Include penicillins and cephalosporins

- Less effective than the preceding drugs

- Although not recommended, frequently used in pregnant patients

Urinary Symptom Relief

Symptoms usually resolve within several days of initiating therapy. In women with severe dysuria, over-the-counter phenazopyridine (Pyridium or Urostat) may reduce symptoms, but scientific evidence of this is lacking [1]. Use of these agents alone could delay the effective diagnosis and treatment. Adverse effects include gastrointestinal upset, rash and blood reactions; kidney damage is also a possibility, but is rare.

Asymptomatic Bacteriuria

Two groups of patients are prone to asymptomatic bacteriuria:- Pregnant women

- The elderly

Pregnancy

Untreated asymptomatic bacteriuria can lead to acute pyelonephritis, possibly resulting in premature delivery and low birth weight [17]. Screening for bacteriuria with a culture should be performed in all pregnant women during the first trimester. The prevalence of bacteria does not change with the occurrence of pregnancy; however, unlike in non-pregnant women, spontaneous resolution of bacteria in pregnant women is unlikely (see Knol, “Urinary Tract Infections - Complicated”). Appropriate antimicrobial treatment will reduce the pregnant patient’s risk of developing acute pyelonephritis from 20-30% to 1-4%, in turn decreasing the risk factors associated with premature delivery and low birth weight [18]. Because trials have reported insufficient evidence, there is no determined duration of antimicrobial treatment for pregnant women with asymptomatic bacteriuria, though 3-7 days is recommended; there is also no recommendation for or against routine repeated screening of culture-negative women later in pregnancy [17].

Elderly Population

In elderly patients, asymptomatic bacteriuria is common. At least 20% of women older than 65 years of age have asymptomatic bacteriuria. A number of factors contribute to bacteriuria in the elderly including:

- Aging

- Catheterization

- Use of antimicrobials

- Debility, e.g., dementia

- Urinary or fecal incontinence

- Decline in immunity

In addition, many patients have underlying structural or functional abnormalities of the urinary tract.

Management

The prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria is particularly high in hospitals and nursing homes. Although some of these patients can develop symptomatic infection, including pyelonephritis and sepsis, these complications are unlikely and there is no evidence that screening for bacteriuria or routine antimicrobial therapy for the prevention or treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria is beneficial. Therefore, asymptomatic bacteriuria in elderly patients should not be treated with antimicrobial agents (17).

However, if the patient has some symptoms, such as change in mental status possibly due to a UTI, or if they develop overt symptoms of a UTI, a urine culture should be obtained. Urinalysis demonstrating pyuria alone is not a good predictor or indication for antimicrobial treatment in this population.

The elderly population is more susceptible than young patients to toxic adverse effects of antimicrobial agents because the metabolism and excretion of these agents can be impaired due to renal or urinary tract abnormalities. Therefore, antimicrobial agents should be used judiciously, and dosing and drug levels carefully monitored.

Need For Evaluation and Referral

Patients whose symptoms resolve promptly and do not recur following antimicrobial therapy do not require further evaluation. However, if the patient’s symptoms are not resolved or recur rapidly, then a medical evaluation including a physical examination, urinalysis, and urine culture should be obtained (Table 2). Physical examination may reveal abnormalities such as vaginitis, urethral mass or urethral diverticulum that could be contributing to the patient’s symptoms and/or infections. Unresolved symptoms may be due to initial or acquired resistance of the bacteria to the drug selected for empiric therapy. Based on cultures, a more appropriate therapy can be selected and the infection hopefully eradicated. If the patient does not have resolution of symptoms and/or recurs with another infection, more extensive counseling and evaluation is indicated, as discussed under recurrent UTIs (see “Knol, Urinary Tract Infections - Complicated”). Several books and other resources describe treatment of uncomplicated UTIs (see “More Information” below).Guidelines [16]

- Most women have uncomplicated UTIs that can be diagnosed by symptoms and urinalysis, and respond to 3 days of antimicrobial therapy

- Urine cultures are not required unless the patient has had recent antimicrobial therapy or symptoms that do not resolve following therapy

- In a managed care setting, young women who do not have symptoms suggesting vaginitis or cervicitis can be treated by telephone consultation [19]

- Uncomplicated UTIs in women should be treated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or trimethoprim for 3 days. If bacterial resistance rates in the community exceed 20%, empiric fluoroquinolone therapy is an option

Key Points

- UTIs are a result of interactions between a uropathogen and the host

- Increased bacterial virulence is required to overcome strong host resistance

- Bacteria with minimal virulence can infect significantly compromised hosts

- Once identified, uncomplicated UTIs can be effectively treated with antimicrobial agents

- Careful consideration should be taken with pregnant women to avoid asymptomatic bacteriuria progression to acute pyelonephritis

- The elderly should not be treated for asymptomatic bacteriuria

More Information

Articles on the Web- New England Journal of Medicine (http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/349/3/259)

- American Family Physician (http://www.aafp.org/afp/20050801/451.html)

- National Guideline Clearinghouse (http://www.guideline.gov/summary/summary.aspx?doc_id=9657)

Books about Urinary Tract Infections

- Stuart L. Stanton and Peter L. Dwyer, Urinary Tract Infection in the Female.

- Elizabeth Kavaler, A Seat on the Aisle, Please!: The Essential Guide to Urinary Tract Problems in Women.

- Joel M.H. Teichman, 20 Common Problems: Urology.

References

- Fihn SD. Clinical practice. Acute uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women. N Engl J Med 2003;349(3):259-66.

- Stamm WE, Hooton TM. Management of urinary tract infections in adults. N Engl J Med 1993;329(18):1328-34

. - Schaeffer AJ, Jones JM, Dunn JK. Association of vitro Escherichia coli adherence to vaginal and buccal epithelial cells with susceptibility of women to recurrent urinary-tract infections. N Engl J Med 1981;304(18):1062-6.

- Sheinfeld J, Schaeffer AJ, Cordon-Cardo C, Rogatko A, Fair WR. Association of the Lewis blood-group phenotype with recurrent urinary tract infections in women. N Engl J Med 1989;320(12):773-7.

- Scholes D, Hooton TM, Roberts PL, Stapleton AE, Gupta K, Stamm WE. Risk factors for recurrent urinary tract infection in young women. J Infect Dis 2000;182(4):1177-82.

- Kunin CM. Sexual intercourse and urinary infections. N Engl J Med 1978;298(6):336-7.

- Fihn SD, Latham RH, Roberts P, Running K, Stamm WE. Association between diaphragm use and urinary tract infection. Jama 1985;254(2):240-5.

- Hooton TM, Scholes D, Hughes JP, et al. A prospective study of risk factors for symptomatic urinary tract infection in young women. N Engl J Med 1996;335(7):468-74.

- Fihn SD, Boyko EJ, Chen CL, Normand EH, Yarbro P, Scholes D. Use of spermicide-coated condoms and other risk factors for urinary tract infection caused by Staphylococcus saprophyticus. Arch Intern Med 1998;158(3):281-7.

- Raz R, Stamm WE. A controlled trial of intravaginal estriol in postmenopausal women with recurrent urinary tract infections. N Engl J Med 1993;329(11):753-6.

- Hurlbut TA, 3rd, Littenberg B. The diagnostic accuracy of rapid dipstick tests to predict urinary tract infection. Am J Clin Pathol 1991;96(5):582-8.

- Stamm WE, Counts GW, Running KR, Fihn S, Turck M, Holmes KK. Diagnosis of coliform infection in acutely dysuric women. N Engl J Med 1982;307(8):463-8.

- Nicolle LE, Harding GK, Preiksaitis J, Ronald AR. The association of urinary tract infection with sexual intercourse. J Infect Dis 1982;146(5):579-83.

- Strom BL, Collins M, West SL, Kreisberg J, Weller S. Sexual activity, contraceptive use, and other risk factors for symptomatic and asymptomatic bacteriuria. A case-control study. Ann Intern Med 1987;107(6):816-23.

- Gupta K, Hooton TM, Stamm WE. Increasing antimicrobial resistance and the management of uncomplicated community-acquired urinary tract infections. Ann Intern Med 2001;135(1):41-50.

- Warren JW, Abrutyn E, Hebel JR, Johnson JR, Schaeffer AJ, Stamm WE. Guidelines for antimicrobial treatment of uncomplicated acute bacterial cystitis and acute pyelonephritis in women. Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Clin Infect Dis 1999;29(4):745-58.

- Nicolle LE, Bradley S, Colgan R, Rice JC, Schaeffer A, Hooton TM. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2005;40(5):643-54.

- Smaill F. Antibiotics for asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001(2):CD000490.

- Fenwick EA, Briggs AH, Hawke CI. Management of urinary tract infection in general practice: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Br J Gen Pract 2000;50(457):635-9.