Illinois: Losing an arm doesn’t have to mean losing all sense of touch, thanks

to prosthetic arms that stimulate nerves with mild electrical feedback. University of Illinois researchers have developed a control algorithm

that regulates the current so a prosthetics user feels steady

sensation, even when the electrodes begin to peel off or when sweat

builds up.

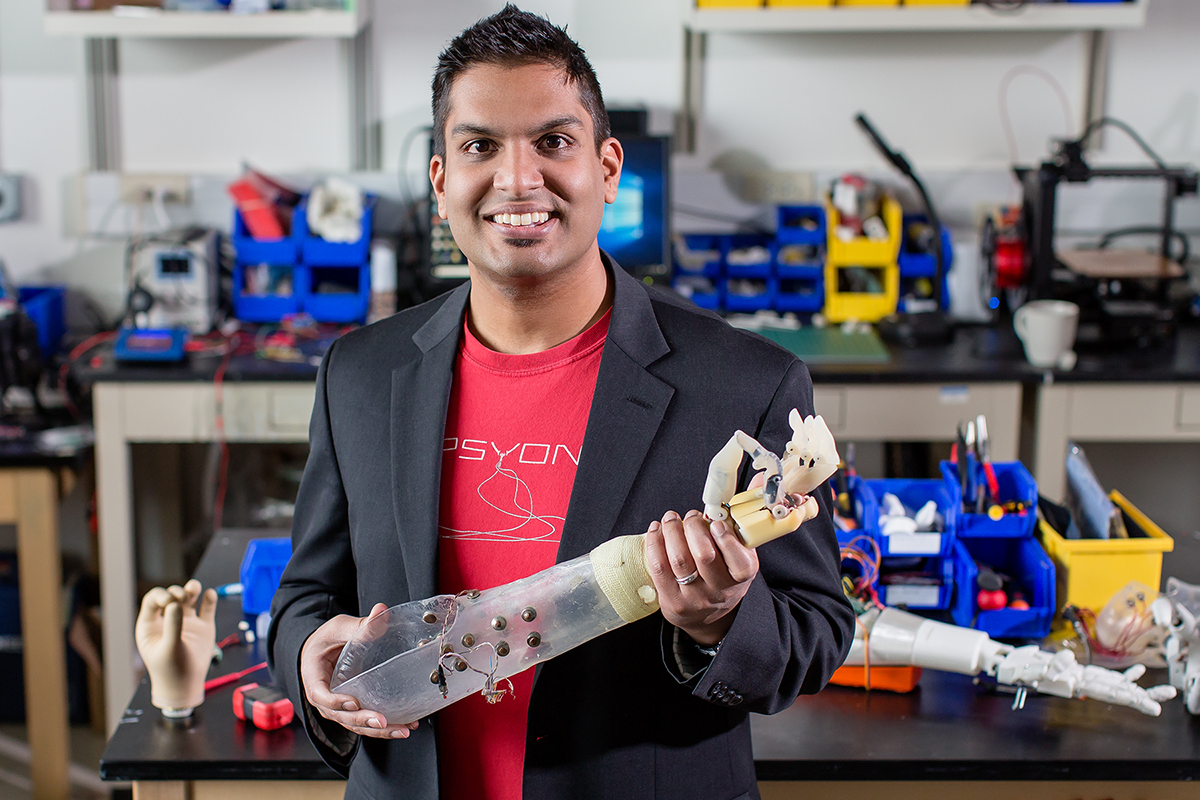

“We’re giving sensation back to someone who’s lost their hand. The

idea is that we no longer want the prosthetic hand to feel like a tool,

we want it to feel like an extension of the body,” said Aadeel Akhtar,

an M.D./Ph.D. student in the neuroscience program and the medical scholars program

at the University of Illinois. Akhtar is the lead author of a paper

describing the sensory control module, published in Science Robotics,

and the founder and CEO of PSYONIC, a startup company that develops low-cost bionic arms.

“Commercial prosthetics don’t have good sensory feedback. This is a

step toward getting reliable sensory feedback to users of prosthetics,”

he said.

Prosthetic arms that offer nerve stimulation have sensors in the

fingertips, so that when the user comes in contact with something, an

electrical signal on the skin corresponds to the amount of pressure the

arm exerts. For example, a light touch would generate a light sensation,

but a hard push would have a stronger signal.

However, there have been many problems with giving users reliable feedback, said aerospace engineering professor Timothy Bretl,

the principal investigator of the study. During ordinary wear over

time, the electrodes connected to the skin can begin to peel off,

causing a buildup of electrical current on the area that remains

attached, which can give the user painful shocks. Alternately, sweat can

impede the connection between the electrode and the skin, so that the

user feels less or even no feedback at all.

“A steady, reliable sensory experience could significantly improve a prosthetic user’s quality of life,” Bretl said.

The controller monitors the feedback the patient is experiencing and

automatically adjusts the current level so that the user feels steady

feedback, even when sweating or when the electrodes are 75 percent

peeled off.

The researchers tested the controller on two patient volunteers. They

performed a test where the electrodes were progressively peeled back

and found that the control module reduced the electrical current so that

the users reported steady feedback without shocks. They also had the

patients perform a series of everyday tasks that could cause loss of

sensation due to sweat: climbing stairs, hammering a nail into a board

and running on an elliptical machine.

“What we found is that when we didn’t use our

controller, the users couldn’t feel the sensation anymore by the end of

the activity. However, when we had the control algorithm on, after the

activity they said they could still feel the sensation just fine,”

Akhtar said.

Adding the controlled stimulation module would cost much less than

the prosthetic itself, Akhtar said. "Although we don't know yet the

exact breakdown of costs, our goal is to have it be completely covered

by insurance at no out-of-pocket costs to users."

The group is working on miniaturizing the module that provides the

electrical feedback, so that it fits inside a prosthetic arm rather than

attaching to the outside. They also plan to do more extensive patient

testing with a larger group of participants.

“Once we get a miniaturized stimulator, we plan on doing more patient

testing where they can take it home for an extended period of time and

we can evaluate how it feels as they perform activities of daily living.

We want our users to be able to reliably feel and hold things as

delicate as a child's hand,” Akhtar said. “This is a step toward making a

prosthetic hand that becomes an extension of the body rather than just

being another tool.”

The National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation supported this work.